How to Write Screenplay – You want to write movie script but where do you start? Do you even know what a movie script is? You see, there are some who believe that the movies are written using computer scripts while some people believe they do it by hand. There are also some beliefs that movies are based on true events while others say it’s just made up stories.

Have you ever wondered how to write movie scripts? Well, you’ve come to the right place. This article by no means covers every aspect and detail of the movie scripts — it is written for beginner writers and focuses mostly on the formats of the scripts.

Table of Contents

What exactly defines a screenplay?

A movie script, also known as a screenplay is a document that ranges anywhere from 70-180 pages. Most movie scripts come in around 110 pages, but there are a number of factors that play into the length.

Before we go too deep into page count, let’s talk about the things you really need to know so that you can get started on your script ASAP.

HOW TO FORMAT A SCREENPLAY

What is standard screenplay format?

Screenplay format is relatively simple, but it’s one of those things that can seem a bit daunting until you’ve actually learned how to do it.

The basics of script formatting are as follows:

- 12-point Courier font size

- 1.5 inch margin on the left of the page

- 1 inch margin on the right of the page

- 1 inch on the of the top and bottom of the page

- Each page should have approximately 55 lines

- The dialogue block starts 2.5 inches from the left side of the page

- Character names must have uppercase letters and be positioned starting 3.7 inches from the left side of the page

- Page numbers are positioned in the top right corner with a 0.5 inch margin from the top of the page. The first page shall not be numbered, and each number is followed by a period.

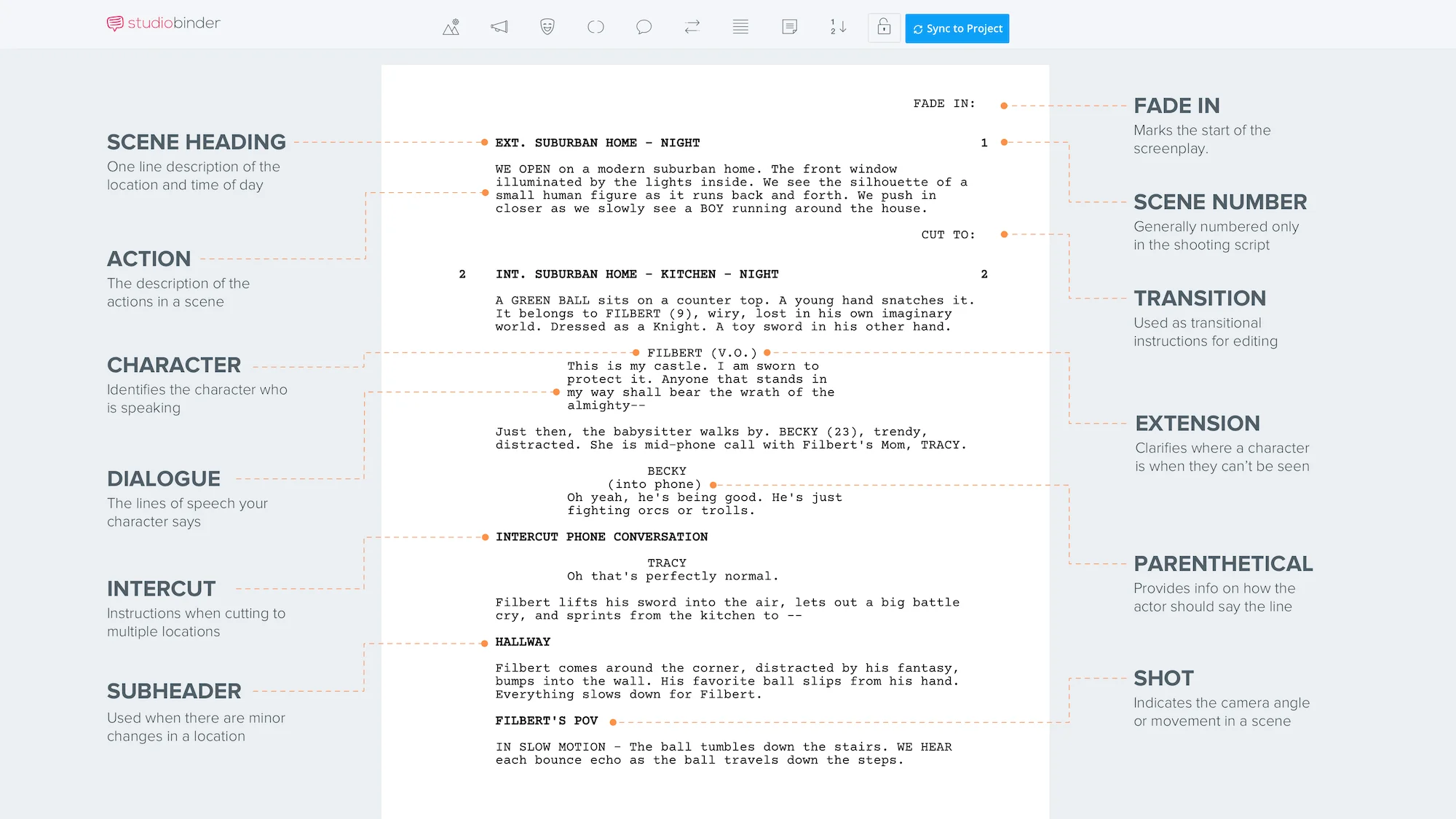

StudioBinder screenwriting software does all the required formating, so you can focus on the creative. Below is a formatted script example:

Script formatting breakdown in StudioBinder

Many scripts begin with a transition, which may include FADE IN: or BLACK SCREEN. Some place this in the top left, others in the top right of the page where many transitions live. Other scripts will begin with scene headings, or even subheadings of imagery they want to front load.

SCENE HEADING

The scene heading is there to help break up physical spaces and give the reader and production team an idea of the story’s geography.

You will either choose INT. for interior spaces or EXT. for exterior spaces. Then a description of the setting, and then the time of day.

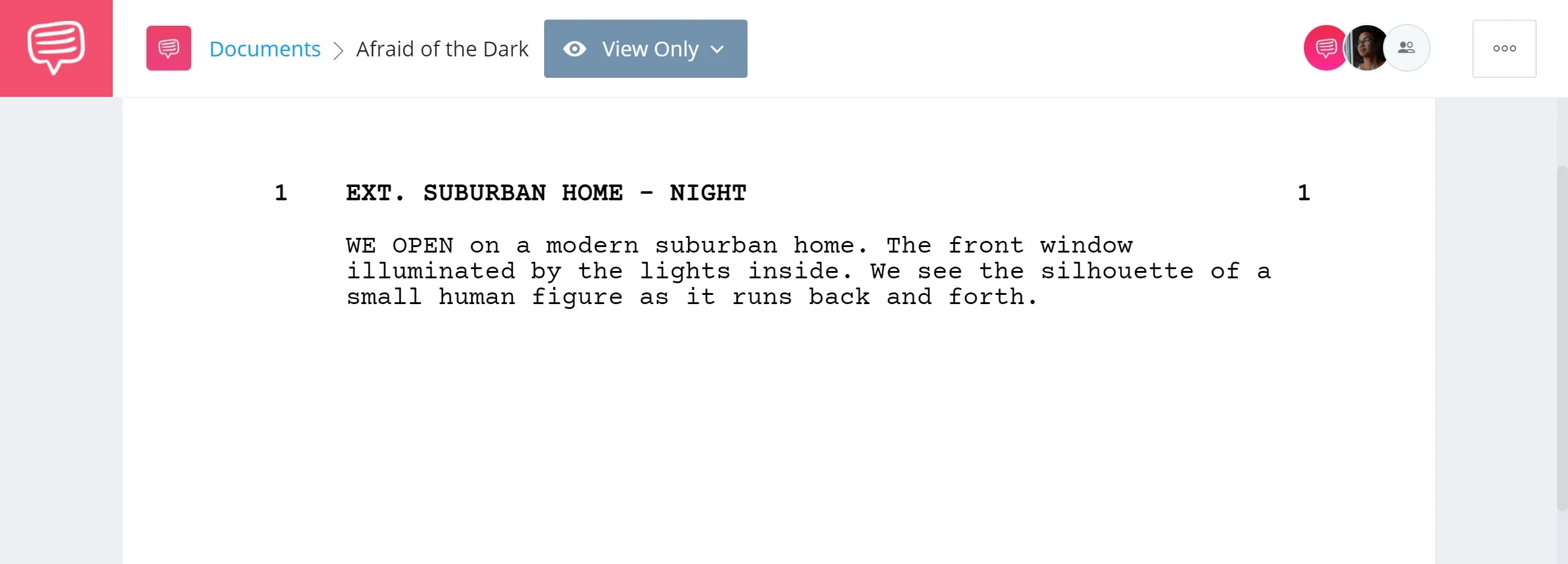

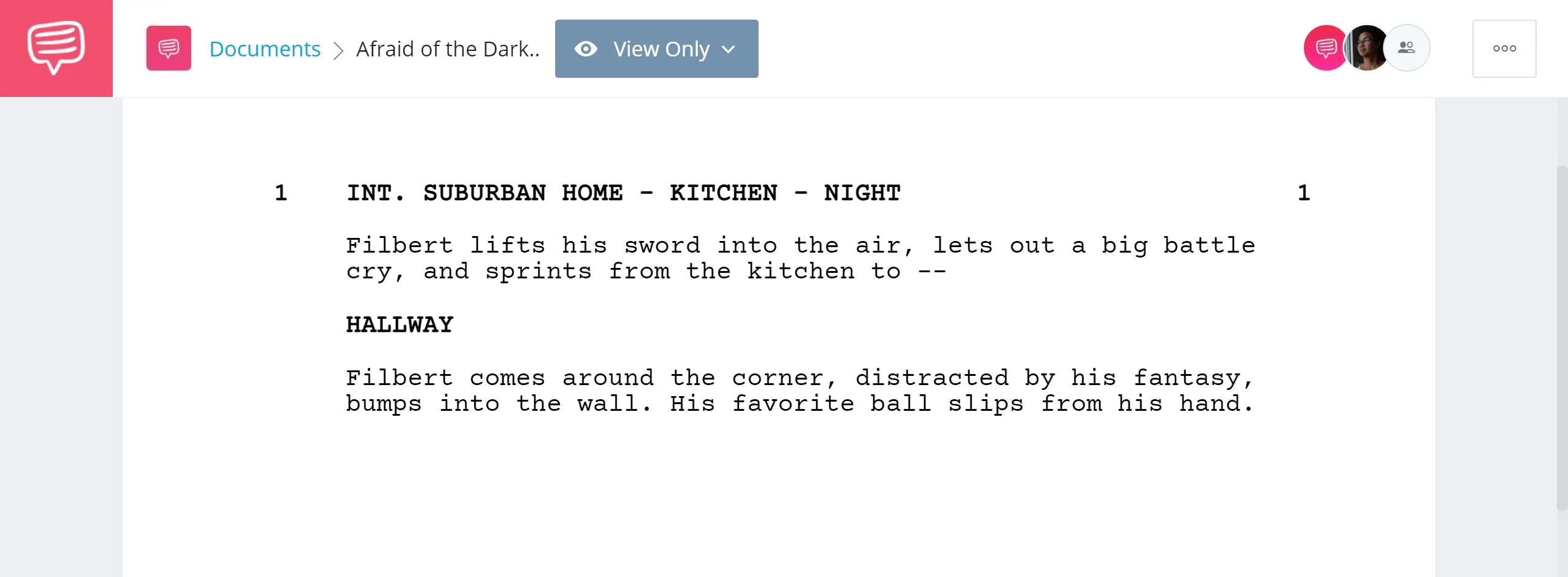

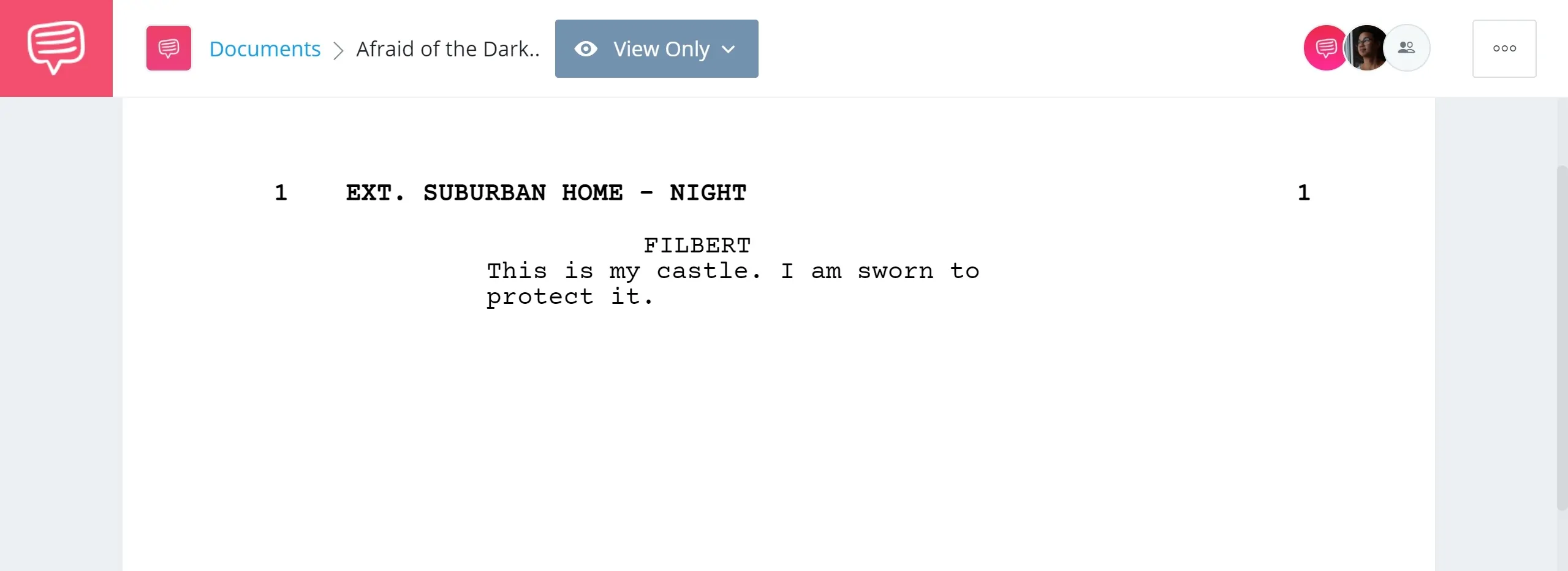

Here’s a screenplay example:

Script format example in StudioBinder Screenplay Writing Software: Scene Heading

There are rare cases where the scene begins inside and goes outside, or vice versa, and in these situations you may write INT/EXT. or EXT/INT.

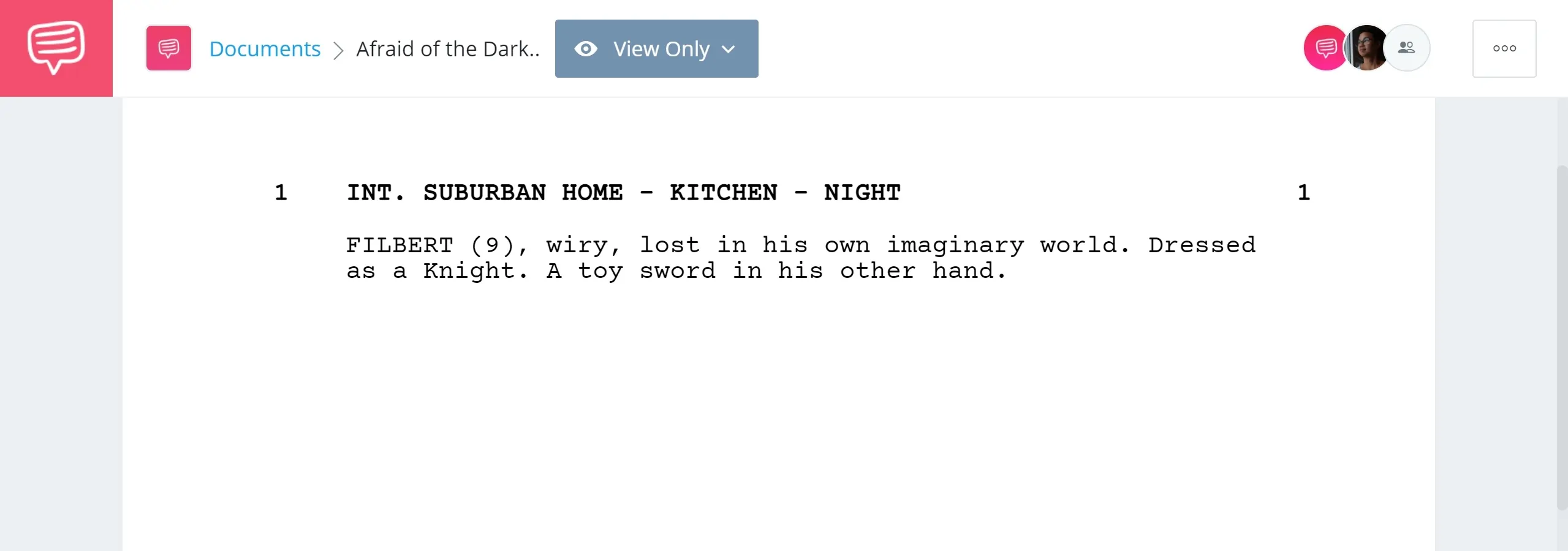

Some scripts take place all around the world, so often screenwriters will use multiple hyphens to give the scene headings even more detail:

Screenplay format example in StudioBinder Screenwriting App: Scene Heading Details

This helps the screenwriter avoid having to point out the geographical location in the action lines, saving space to write more about the actual story and keep readers engaged in the story… not the formatting.

SUBHEADING

Often, writers will use subheadings to show a change in location without breaking the scene, even if the scene has shifted from INT. to EXT.

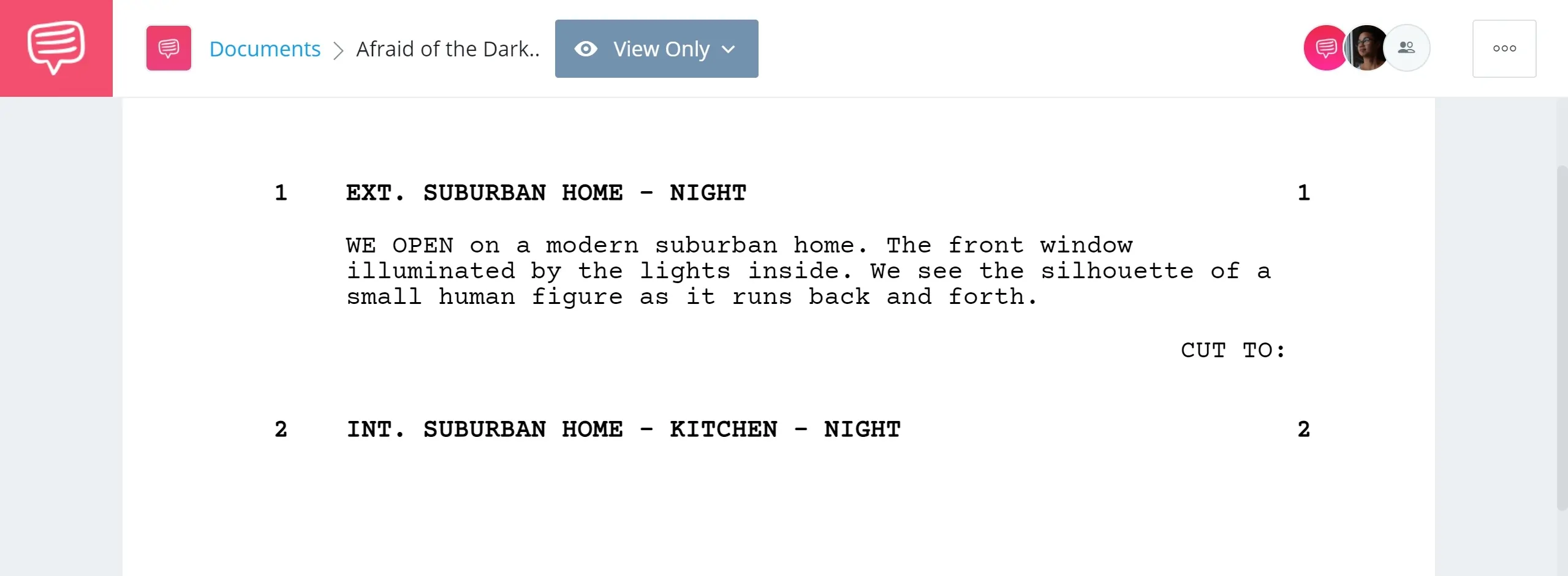

Here’s a script example:

Script formatting example in StudioBinder Sciptwriting Software: Scene Subheading

It is assumed that readers will understand the change in space while retaining the idea that the time of day is the same – even continuous.

The reason many writers do this is to avoid the notion that we’ve entered an entirely new scene, though you could always include CONTINUOUS in place of DAY or NIGHT by creating an entirely new scene heading.

It’s a matter of personal style and rhythm vs. production considerations.

TRANSITIONS

In the bottom right of the page you will place transitions, but in modern screenwriting these seem to be used less and less. The transitions that seems to have really stood the test of time are CUT TO: and FADE OUT.Here’s a screenplay example:

Screenplay formatting example in StudioBinder Sciptwriting Software: Scene Transition

You may also include something like DISSOLVE TO:, but these are used less and less, probably for the same reason you avoid camera shots.

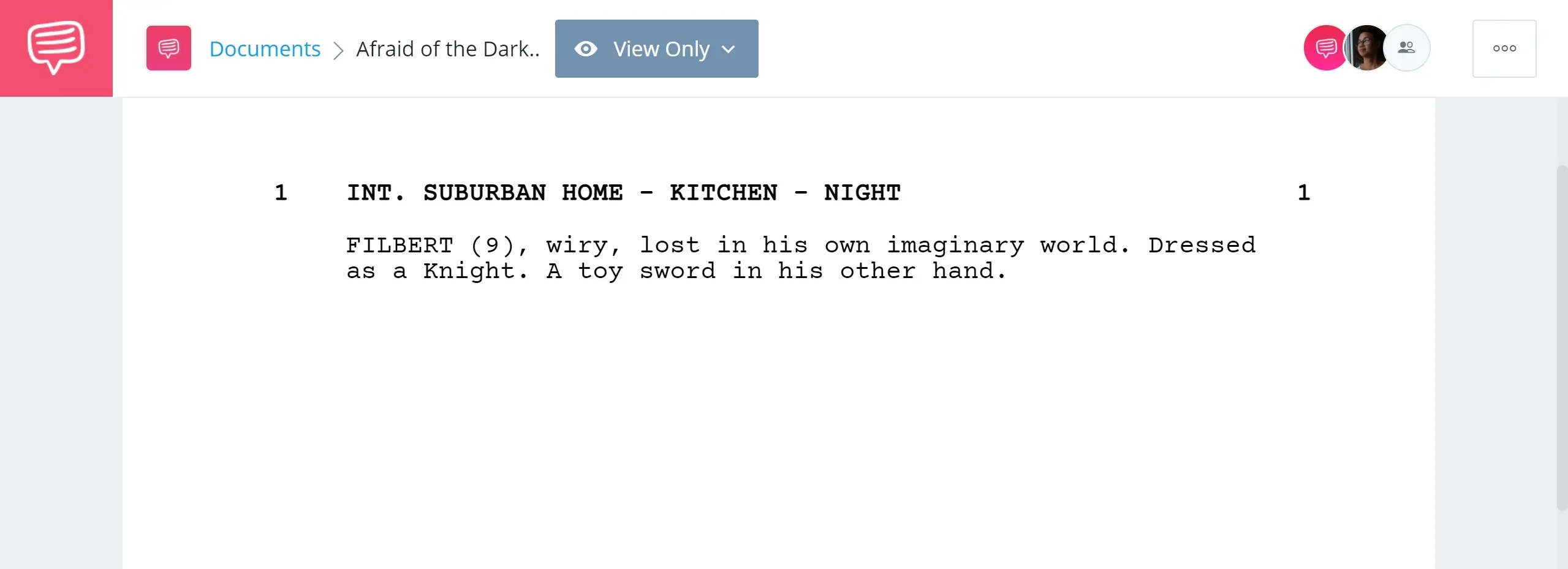

CHARACTER INTRODUCTIONS

When you introduce a character in a screenplay, you want to use all-capital letters for the name of the character, then a reference to their age, and finally some information about their traits and personality.

Here’s a screenplay example:

Script format example in StudioBinder Scriptwriting Software: Character Introduction

Again, screenwriters have found other ways to do this, but this is the most common and production friendly way to introduce a character.

We have a post on how to introduce characters in a screenplay that goes into the creative considerations of introducing characters, so I highly recommend you check it out after this post to learn more.

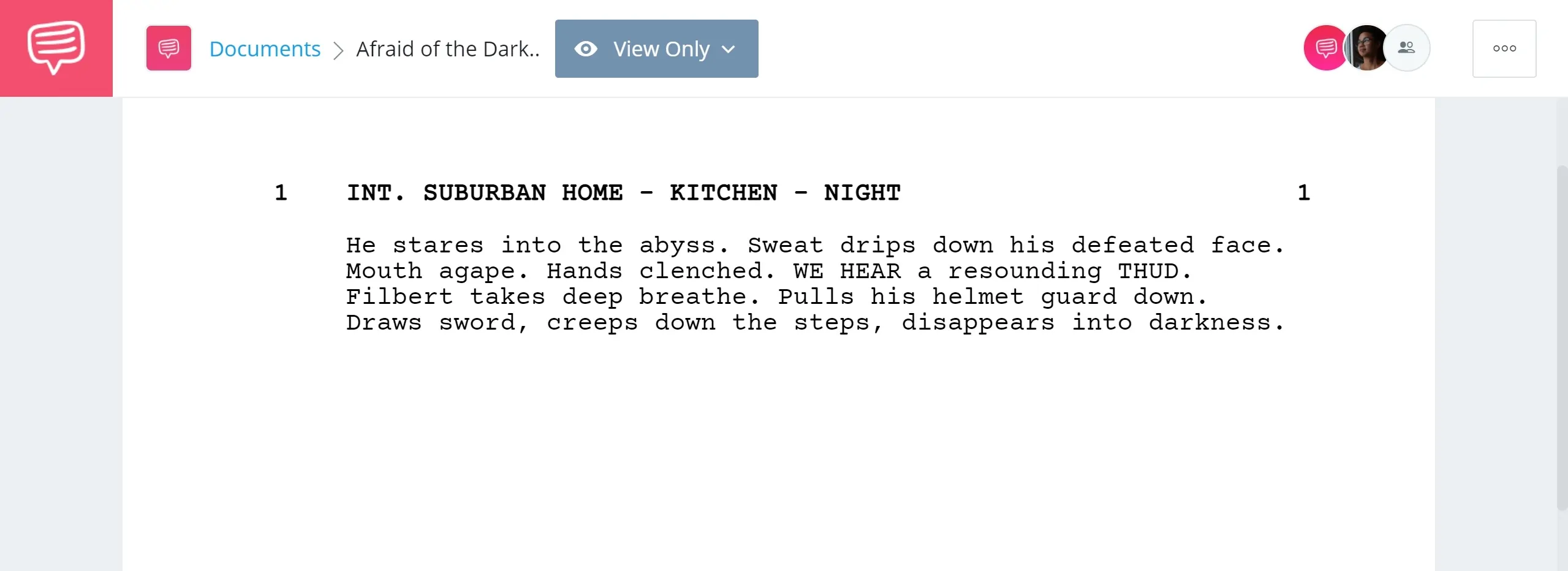

ACTION

Action lines are where you describe the visual and audible actions that take place on screen. You want to write in third person in present tense.

Here’s a script example:

Script format example in StudioBinder Screenwriting Solution: Action Lines

Often, you can make your script a better read by eliminating redundant pronouns and conjunctions. Big sounds and important objects can be written out in ALL CAPS to emphasize their effect on the story.

DIALOGUE

Your lines of dialogue will be set underneath the character to which they are assigned. Dialogue is pretty straightforward from a formatting standpoint, but it is the most difficult part of screenwriting.

Script format example in StudioBinder Free Screenwriting App: Dialogue Lines

If you want to learn more, check out our post on 22 Screenwriting Tips for Writing Better Dialogue where I go over a bunch of ways to audit your screenplay for good… and bad dialogue.

EXTENSIONS

These occur when a character says something off-screen (O.S.), or if dialogue is voice-over (V.O.). You will see extensions when a character ends a block of dialogue, performs an action, and speaks more.

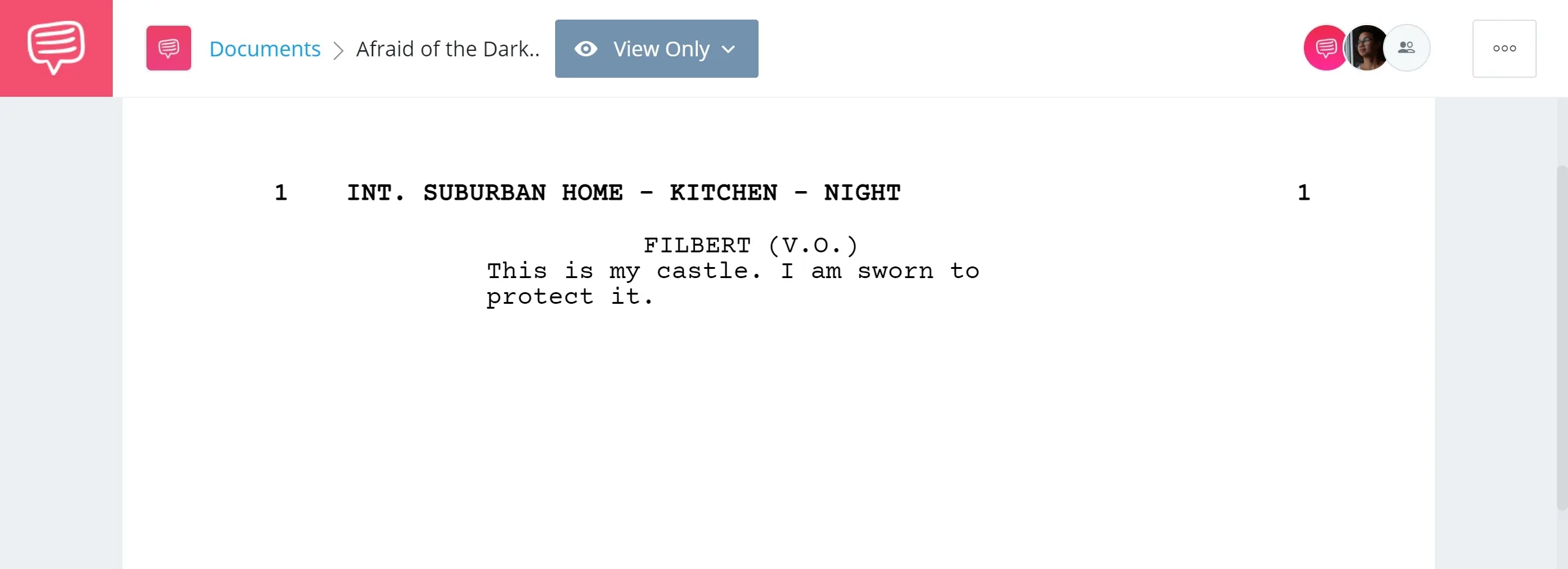

Here’s a script example:

Screenplay format example in StudioBinder Web-Based Scriptwriting Software: Extensions

This takes the form of continued (CONT’D). Professional script writing software will help you with this, but it will not be able to predict when you want something said off screen or in voice-over.

PARENTHETICAL

You can use a parenthetical inside your dialogue to show small actions, or even a change in mood without having to jump out to an action line.

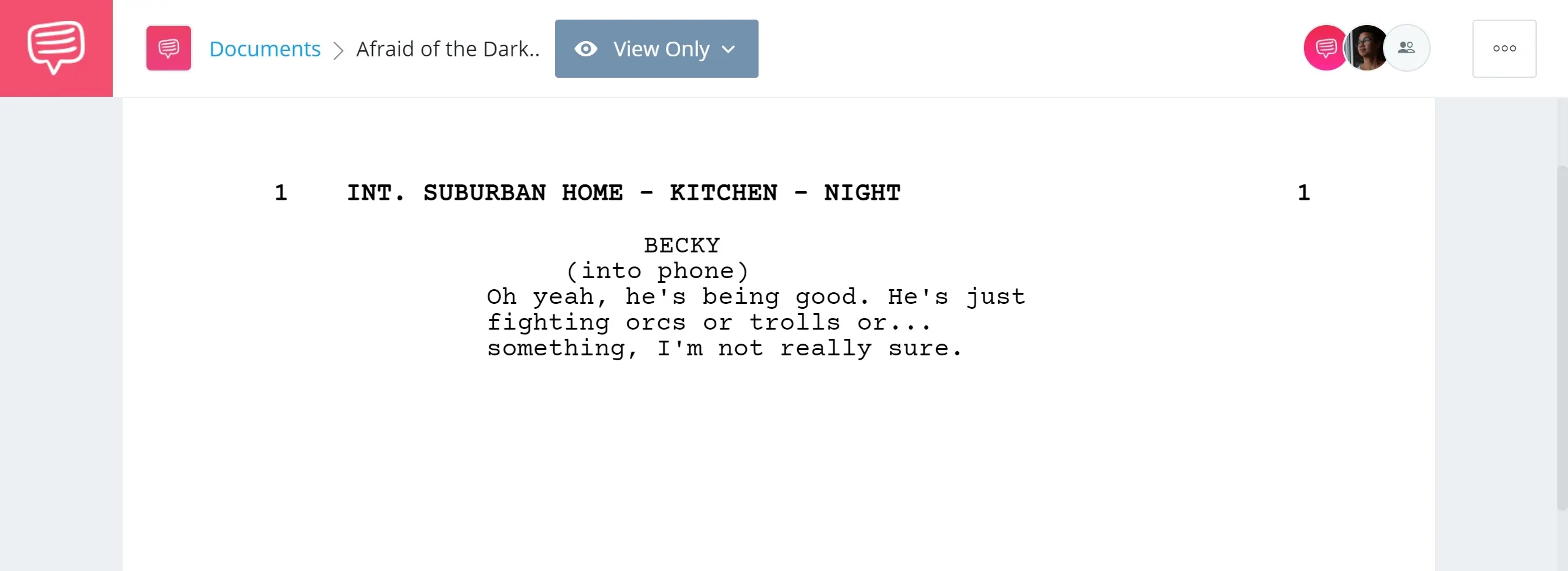

Here’s a screenplay example:

Script format example in StudioBinder Free Script Writing Software: Parenthetical

Parentheticals are really good for directing actors, and adding sarcasm and nuance to performances on the page, but you may want to be cautious about adding them too much. Actors are professionals, and if Al Pacino finds parentheticals in a script, he may get his feelings hurt.

CAMERA SHOTS

The best professional screenwriters know how to suggest shots without actually writing in shots, but if you really insist on describing a particular shot in your screenplay you can format it like a subheading.

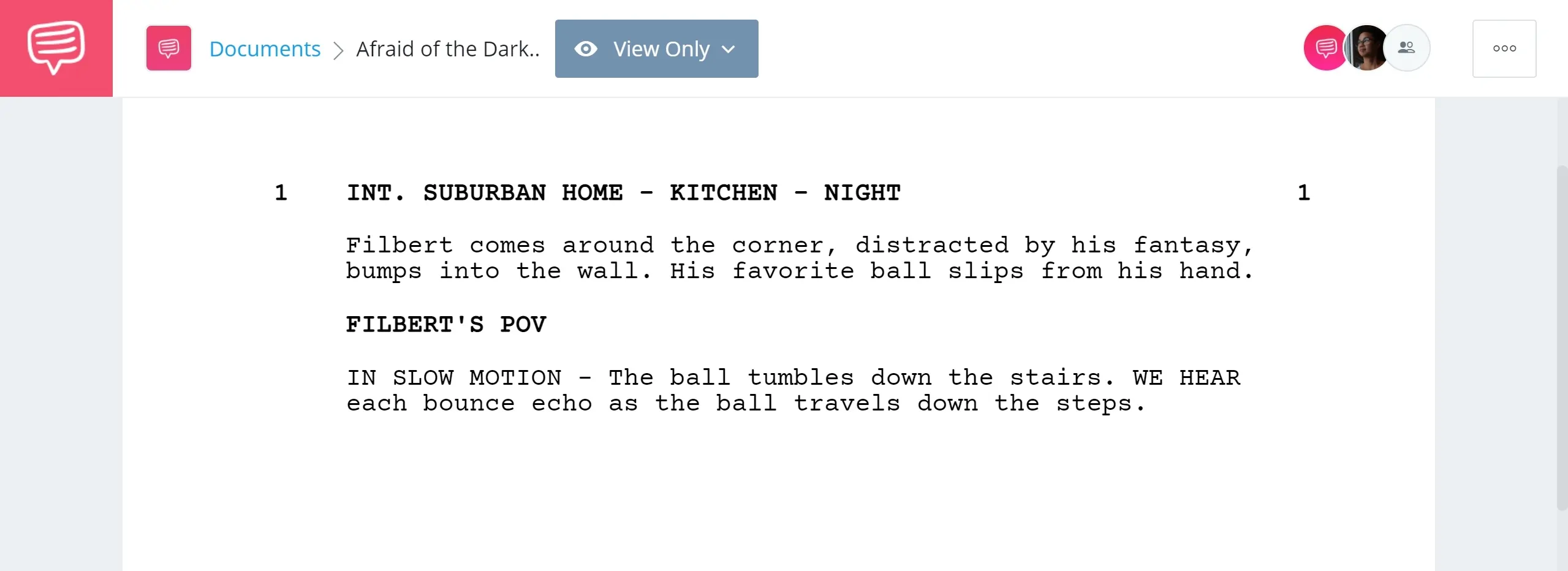

Here’s a script example

Script format example in StudioBinder Online Screenwriting Software: Camera Shot

This lets us know that the shot is supposed to be set so that we see things from Filbert’s perspective. Writing out shots is often frowned upon, but if you’re directing the film, maybe do it sparingly.

How to Write Movie Scripts

Part 1: Creating a Story World

- Think of a theme or conflict that you want to tell in your story. Use a “What if?” question to form the idea of your script. Start taking inspiration from the world around you and ask yourself how it would be affected by a specific event or character. You may also think about an overall theme, such as love, family, or friendship for your story so that your whole script is tied together.

- For example, “What if you went back in time and met your parents when they were your age?” is the premise for Back to the Future, while “What if a monster rescued a princess instead of a handsome prince?” is the premise to Shrek.

- Carry a small notebook with you wherever you go so you can take down notes when you get ideas.

- Pick a genre for your story. Genre is an important storytelling device that lets readers know what sort of story to expect. Look at the movies or TV shows that you enjoy most and try to write a script in a similar style.

- Combine genres to make something unique. For example, you may have a western movie that takes place in space or a romance movie with horror elements.Picking a GenreIf you like big set pieces and explosions, consider writing an action film.If you want to scare other people, try writing a horror script.If you want to tell a story about a relationship, try writing a drama or romantic comedy.If you like a lot of special effects or what could happen in the future, write a science fiction film.

- Choose a setting for your script to take place. Make sure the setting works with the story or theme of your script. Make a list of at least 3-4 different settings for your characters to travel between in your script so it stays interesting.

- For example, if one of your themes is isolation, you may choose to set your script in an abandoned house.

- The genre you pick will also help you choose your setting. For example, it’s unlikely that you’d set a western story in New York City.

- Make an interesting protagonist. When you’re making a protagonist, give them a goal that they are trying to achieve throughout the script. Give your character a flaw, such as being a constant liar or only thinking for themselves, to make them more interesting. By the end of your script, your character should go through an arc and change in some way. Brainstorm who your character is at the beginning of the story versus how the events would change them.

- Don’t forget to figure out a memorable name for your character!

- Create an antagonist that opposes your protagonist. The antagonist is the driving force that goes against your protagonist. Give your protagonist and antagonist similar qualities, but change the way the antagonist approaches them. For example, your protagonist may be trying to save the world, but the antagonist may think the only way to save it is to destroy it.

- If you’re writing a horror story, your antagonist may be a monster or a masked killer.

- In a romantic comedy, the antagonist is the person your main character is trying to woo.

- Write a 1-2 sentence logline to summarize the plot of your script. A logline is a short summary of the main events in your film. Use descriptive language to help your logline sound unique so other people understand what the main ideas of your story are. Make sure the conflict is present in your logline.

- For example, if you wanted to write a logline for the movie A Quiet Place, you may say, “A family is attacked by monsters,” but it doesn’t give any details. Instead, if you wrote, “A family must live in silence to avoid being captured by monsters with ultra-sensitive hearing,” then the person reading your logline understands the main points of your script.

Part 2: Outlining Your Script

- Brainstorm plot ideas on index cards. Write down each event in your script on their own note cards. This way you can easily reorganize the events to see what works best. Write down all of your ideas, even if you think they’re bad, since you may not know what will work best in your final script.

- If you don’t want to use index cards, you may also use a word document or screenwriting software, such as WriterDuet or Final Draft.

- Arrange the events in the order you want them in your script. Once you write all of your ideas on cards, lay them out on a table or floor and organize them in the chronological order of your story. Look at how certain events lead into one another to see if it makes sense. If it doesn’t, set the index cards aside to see if they’d work somewhere better in your outline.

- Have events in the future take place early in your film if you want to make a mind-bending movie with twists, such as Inception.

- Ask yourself the importance of each scene you want to include. As you go through your outline ask yourself questions, such as, “What is the main point of this scene?” or, “How does this scene move the story forward?” Go through each of the scenes to see if they add to the story or if they’re only there to fill out space. If the scene doesn’t have a point or move the story, you can probably remove it.

- For example, if the scene is your character just shopping for groceries, it doesn’t add anything to the story. However, if your character bumps into someone at the grocery store and they hold a conversation related to the main idea of the movie, then you can keep it.

- Use high and low moments as your act breaks. Act breaks help separate your story into 3 parts: setup, confrontation, and resolution. The setup, or Act I, begins at the start of your story and ends when your character makes a choice that changes their lives forever. Throughout the confrontation, or Act II, your protagonist will work towards their goal and interact with your antagonist leading up to the climactic point of the story. The resolution, or Act III, takes place after the climax shows what happens afterward.[9]Tip: TV scripts usually hit act breaks when they cut to commercials. Watch shows similar to the story you’re writing to see what happens just before they go to a commercial break.

Part 3: Formatting the Script

- Create a title page for your script. Include the title of your script in all caps in the center of the page. Put a line break after the title of your script, then type “written by.” Add another line break before typing your name. Leave contact information, such as an email address and phone number in the bottom left margins.

- If the script is based on any other stories or films, include a few lines with the phrase “Based on the story by” followed by the names of the original authors.

- Use size 12 Courier font throughout your whole script. Screenwriting standard is any variation of Courier so it’s easy to read. Make sure to use 12-point font since it’s what other scripts use and is considered industry standard.

- Use any additional formatting, such as bolding or underlining, sparingly since it can distract your reader. Tip: Screenwriting software, like Celtx, Final Draft, or WriterDuet, all automatically format your script for you so you don’t need to worry about changing any settings.

- Put in scene headings whenever you go to a different location. Scene heading should be aligned to the left margin 1 1⁄2 in (3.8 cm) from the edge of the page. Type the scene headings in all caps so they’re easily recognizable. Include INT. or EXT. to tell readers if the scene takes place inside or outside. Then, name the specific location followed by the time of day it takes place.

- For example, a scene heading may read: INT. CLASSROOM – DAY.

- Keep scene headings on a single line so they aren’t too overwhelming.

- If you want to specify a room in a specific location, you can also type scene headings like: INT. JOHN’S HOUSE – KITCHEN – DAY.

- Write action blocks to describe settings and character actions. Action blocks should be aligned with the left margin and are written in regular sentence structure. Use action lines to denote what a character does and to give brief descriptions about what’s happening. Keep action lines brief so they don’t overwhelm a reader looking at the page.

- Avoid writing what the characters are thinking. A good rule of thumb to think about is if it can’t be seen on a screen, don’t include it in your action block. So instead of saying, “John thinks about pulling the lever but he’s not sure if he should,” you may write something like, “John’s hand twitches near the lever. He grits his teeth and furrows his brow.”

- When you introduce a character for the first time in an action block, use all caps for their name. Every time after you mention the character name, write it as normal.

- Center character names and dialogue whenever a character speaks. When a character is about to speak, make sure the margin is set to 3.7 in (9.4 cm) from the left side of the page. Put the characters name in all caps so a reader or actor can easily see when their lines occur. When you write the dialogue, make sure it’s 2 1⁄2 in (6.4 cm) from the left side of the page.

- If you want to make it clear how your character is feeling, include a parenthetical on the line right after the character name with an emotion. For example, it may read (excited) or (tense). Make sure the parenthetical is 3.1 in (7.9 cm) from the left side of the page.

Part 4: Writing Your First Draft

- Set a deadline so you have a goal to reach. Choose a date that’s about 8-12 weeks away from when you start since these are the usual industry times that writers have to work on a script. Mark the deadline on a calendar or as a reminder on your phone so it holds you accountable for working on your script.

- Tell others about your goal and ask them to hold you accountable for finishing your work.

- Plan to write at least 1-2 pages per day. During your first draft, just write the ideas that come to your head and follow along with your outline. Don’t worry about spelling or grammar entirely since you just need to get your story written down. If you aim to do 1-2 pages each day, you’ll finish your first draft within 60-90 days.

- Choose a set time each day to sit down and write so you don’t get distracted.

- Turn off your phone or internet connection so you can just focus on writing.

- Say your dialogue out loud to see if it sounds natural. As you write what your characters are saying, talk through it out loud. Make sure it flows well and doesn’t sound confusing. If you notice any problem areas, highlight or underline the phrases and come back to them next time you edit.[16]

- Make sure each character sounds different and has a unique voice. Otherwise, a reader will have a hard time distinguishing between who’s speaking.

- Keep writing until you’re between 90-120 pages. Think of each page equalling 1 minute of screen time. To write a standard film script, aim to write something about 90-120 pages long so it would run for 1 ½-2 hours long.

- If you’re writing a TV script, aim for 30-40 pages for a half-hour sitcom and 60-70 pages for an hour-long drama.

- Short films should be about 10 pages or less.

Part 5: Revising Your Script

- Take a 1-2 week break from your script when you finish it. Since you’ve been working on your script for a long period of time, save the file and focus on something else for a few weeks. That way, when you come back to edit it, you’ll be able to look at it with fresh eyes.

- Start work on another script while you wait if you want to keep working on other ideas.

- Reread your entire script and take notes on what doesn’t make sense. Open your script and read it from start to end. Look for places where the story is the confusing or where characters are doing things without moving the story forward. Write your notes down by hand so you can remember them better.

- Try to read your script out loud and don’t be afraid to act out parts based on how you think they should be performed. That way, you can catch dialogue or wording that doesn’t work as well. Tip: If you can, print out your screenplay so you can directly write on it.

- Share your script with someone you trust so they can look over it. Ask a friend or parent to look over your script to see what they think. Tell them what sort of feedback you’re looking for so they know what to focus on. Ask them questions when they’re finished about whether parts make sense or not.

- Keep rewriting the script until you’re happy with it. Work on story and character revisions first to fix larger problems in your script. As you work through each revision, work from larger problems, such as dialogue or confusing action sequences, to minor problems, such as grammar and spelling.

- Start each draft in a new document so you can cut and paste parts you like from your old script into the new one.

- Don’t get too nit-picky with yourself or you’ll never finish the script you’re working on.

Conclusion

Did you know that for every second of screen time there are seven minutes of script to be written? Movie scripts look more intimidating than they really are. They are basically a collection of action, narration, and dialogue.