How to Write in Chinese – If you’re interested in reading and writing Chinese characters, there’s no better place to get started than with the numbers 1-10. They are quite simple to write, useful to know, and are exactly the same in both the traditional and simplified writing systems.

Table of Contents

First Steps in Learning Chinese Characters

When learning a European language, you have certain reference points that give you a head start.

If you’re learning French and see the word l’hotel, for example, you can take a pretty good guess what it means! You have a shared alphabet and shared word roots to fall back on.

In Chinese this is not the case.

When you’re just starting out, every sound, character, and word seems new and unique. Learning to read Chinese characters can feel like learning a whole set of completely illogical, unconnected “squiggles”!

The most commonly-taught method for learning to read and write these “squiggles” is rote learning.

Just write them again and again and practise until they stick in your brain and your hand remembers how to write them! This is an outdated approach, much like reciting multiplication tables until they “stick”.

I learnt this way.

Most Chinese learners learnt this way.

It’s painful…and sadly discourages a lot of learners.

However, there is a better way.

Even without any common reference points between Chinese and English, the secret is to use the basic building blocks of Chinese, and use those building blocks as reference points from which to grow your knowledge of written Chinese.

This article will:

- Outline the different levels of structure inherent in Chinese characters

- Show you how to build your own reference points from scratch

- Demonstrate how to build up gradually without feeling overwhelmed

The Structure Of Written Chinese

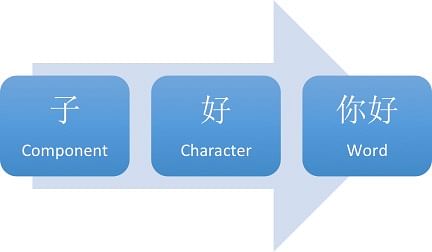

The basic structure of written Chinese is as follows:

I like to think of Chinese like Lego... it’s very “square”!

The individual bricks are the components (a.k.a radicals).

We start to snap these components together to get something larger – the characters.

We can then snap characters together in order to make Chinese words.

Here’s the really cool part about Chinese: Each of these pieces, at every level, has meaning.

The component, the character, the word… they all have meaning.

This is different to a European language, where the “pieces” used to make up words are letters.

Letters by themselves don’t normally have meaning and when we start to clip letters together we are shaping a sound rather than connecting little pieces of meaning. This is a powerful difference that comes into play later when we are learning vocabulary.

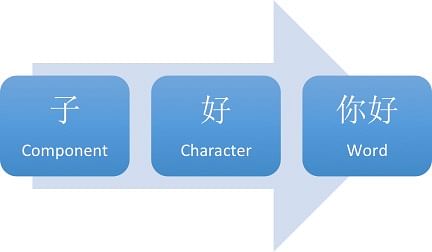

Let’s look at the diagram again.

Here we start with the component 子. This has the meaning of “child/infant”.

The character 好 (“good”) is the next level. Look on the right of the character and you’ll see 子. We would say that 子 is a component of 好.

Now look at the full word 你好 (“Hello”). Notice that the 子 is still there.

- The character 好 is built of the components 女 and 子.

- The character 你 is built from 人 + 尔.

- The word 你好 in turn is constructed out of 你 + 好.

Here’s the complete breakdown of that word in an easy-to-read diagram:

Now look at this photo of this in real life!

Don’t worry if you can’t understand it. Just look for some shapes that you have seen before.

The font is a little funky, so here are the typed characters: 好孩子

What components have you seen before?

Did you spot them?

This is a big deal.

Here’s why…

Why Character Components Are So Important

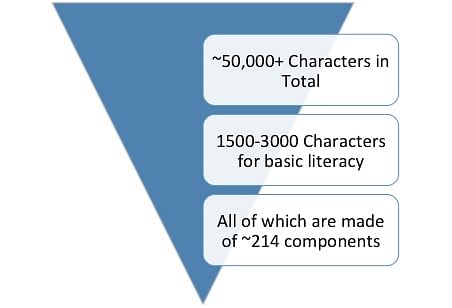

One of the big “scare stories” around Chinese is that there are 50,000 characters to learn.

Now, this is true. But learning them isn’t half as bad as you think.

Firstly, only a few thousand characters are in general everyday use so that number is a lot more manageable.

Second, and more importantly, those 50,000 characters are all made up of the same 214 components.

And you already know one of them: 子 (it’s one of those 214 components).

The fact that you can now recognise the 子 in the image above is a huge step forward.

You can already recognise one of the 214 pieces all characters are made up of.

Even better is the fact that of these 214 components it’s only the 50-100 most common you’ll be running into again and again.

This makes Chinese characters a lot less scary.

Once you get a handle on these basic components, you’ll quickly recognise all the smaller pieces and your eyes will stop glazing over!

This doesn’t mean you’ll necessarily know the meaning or how to pronounce the words yet (we’ll get onto this shortly) but suddenly Chinese doesn’t seem quite so alien any more.

Memorising The Components Of Chinese Characters

Memorising the pieces is not as important as simply realising that ALL of Chinese is constructed from these 214 pieces.

When I realised this, Chinese became a lot more manageable and I hope I’ve saved you some heartache by revealing this early in your learning process!

Here are some useful online resources for learning the components of Chinese characters:

- An extensive article about the 214 components of Chinese characters with a free printable PDF poster.

- Downloadable posters of all the components, characters and words.

- If you like flashcards, there’s a great Anki deck here and a Memrise course here.

- Wikipedia also has a sweet sortable list here.

TAKEAWAY: Every single Chinese character is composed of just 214 “pieces”. Only 50-100 of these are commonly used. Learn these pieces first to learn how to write in Chinese quickly.

Moving From Components To Chinese Characters

Once you’ve got a grasp of the basic building blocks of Chinese it’s time to start building some characters!

We used the character 好 (“good”) in the above example. 好 is a character composed of the components 女 (“woman”) and 子 (“child”).

Unlike the letters of the alphabet in English, these components have meaning.

(They also have pronunciation, but for the sake of simplicity we’ll leave that aside for now!)

- 女 means “woman” and 子 means “child”.

- When they are put together, 女 and 子 become 好 …and the meaning is “good”.

- Therefore “woman” + “child” = “good” in Chinese 🙂

When learning how to write in Chinese characters you can take advantage of the fact that components have their own meanings.

In this case, it is relatively easy to make a mnemonic (memory aid) that links the idea of a woman with her baby as “good”.

Because Chinese is so structured, these kind of mnemonics are an incredibly powerful tool for memorisation.

Some characters, including 好, can also be easily represented graphically. ShaoLan’s book Chineasy does a fantastic job of this.

Here’s the image of 好 for instance – you can see the mother and child.

Visual graphics like these can really help in learning Chinese characters.

Unfortunately, only around 5% of the characters in Chinese are directly “visual” in this way. These characters tend to get the most attention because they look great when illustrated.

However, as you move beyond the concrete in the more abstract it becomes harder and harder to visually represent ideas.

Thankfully, the ancient Chinese had an ingenious solution, a solution that actually makes the language a lot more logical and simple than merely adding endless visual pictures.

1. A basic introduction of Chinese characters

Chinese characters are relatively independent from the phonetic system. There are about 80,000 characters in total and about 6,500 which are used daily. Each character has its own pronunciation, though many of them share the same pinyin syllables. The large number may make many beginners feel scared and overwhelmed. Actually, after knowing the principle of making characters and the rules behind it, mastering the writing of characters should be quite easy. It`s like a “one formula fits all” method.

Traditional or Simplified characters?

We all know that there are two versions of Chinese characters in us nowadays: traditional Chinese characters (繁体字)and simplified Chinese characters (简体字). The traditional version is mainly used in Hongkong, Taiwan, Singapore, and a several other places. The simplified version is mainly used in mainland China. No matter which version you choose to learn, the rules of writing are the same. So, in learning how to write, the version you wish to learn doesn’t really matter.

2. Character formation

Obviously, such a large number of characters cannot be made randomly. Following certain rules, these characters which have grown over thousands of years are still very dynamic.

The formation of characters seems just like a “LEGO” game! There are many small components, and you just need to put the small components together and give them order. Each of the components are made of smaller strokes.

Strokes

The strokes of Chinese characters refer to one uninterrupted dot or line, such as “一”(横)、“丨”(竖)、 “丿”(撇)、“丶”(点)、“乛”(折), etc. A stroke is the smallest component of a character. There are 8 traditional fundamental strokes, which are “丶”(点)、“一”(横)、“丨”(竖)、 “丿”(撇)、 “乀” (捺)、 “㇀”(提)、 “乛” (折) and “亅” (钩).It`s also called “’永’字八法” (yǒngzìbāfǎ). The character “永” basically represents the common stroke types of the Chinese character system.

The modern modular strokes are regulated as the 5 one’s, “一”(横)、“丨”(竖)、 “丿”(撇)、“丶”(点)and“乛” (折), and they are called “’札’字法” (zházìfǎ). It`s a simpler version of “’永’字八法”.

Radicals

Radicals in Chinese characters are called 部首[bùshǒu]. They are used to classify the character patterns which are commonly used in Chinese dictionaries. There are mainly two types of radicals depending on their different functions and properties. One is based on the principles of the six categories of Chinese characters (which we will illustrate more in the content that follows), and the other is based on the shapes of the structures.

Once you understand the relations among strokes, radicals, and characters, writing characters becomes a piece of cake. Moreover, you can not only imitate drawing the shapes, but also understand the underlying rules and reasons behind the characters. Of course, practicing with understanding would be a much better way than mechanical imitation.

Let`s take “女” as an example. “女” is not only a independent character which means female, but it is also a radical which can be combined with other Chinese components and indicates some certain meanings. As the following picture shows, “妈”“姐”“妹” are all females, thus they share the same radical while the right sides are diversified because of the phonetics.

The categories of Chinese characters

There are six main categories of Chinese characters: Pictographs (象形字), Pictophonetic characters (形声字), Simple ideograms(指示字), Compound ideographs (会意字), Phonetic loan characters (假借字), and Derivative cognates (转注字). Here, I will introduce the four commonly used categories:

1). Pictographs (象形字)

These are stylised drawings of the objects they represent. Many Chinese learners feel that they are “drawing” Chinese characters, and in this case, they are! Most of the single characters and radicals are from this category.

2) Pictophonetic characters (形声字)

They are also called radical-phonetic characters. Over 70% of Chinese characters were created by this method. There are mainly two components: the phonetic component and the semantic component. The “女” radical we mentioned before is a typical example of this category.

e.g.

女 à the meaning part (also the radical), “female”

“妈”“姐”“妹” à“马” “且” “未” indicate the phonetic part.

3) Simple ideograms(指示字)

These express an abstract idea through an iconic form. For example, the numbers in Chinese, “一” “二” “三”, are represented by the appropriate number of strokes which means “one” “two” “three”.

4) Compound ideographs (会意字)

These are the combination of two or more pictographic characters to suggest the meaning of the character to be represented.

e.g.

木(mù) à wood

林(lín) à woods (two 木)

森(sēn) à forest (three 木)

3. The Basic Writing Order

Stroke order really matters if you want to learn writing characters. Using the wrong stroke order or direction would cause the ink to fall differently on the page. The Chinese stroke order system was designed to produce the most aesthetical, symmetrical, and balanced characters on a piece of paper. Furthermore, it was also designed to be efficient – creating the most strokes with the least amount of hand movement across the page. Here, I`ll quote the rules that Sara once wrote in the article Why Chinese Stroke Order is Important and How to Master it at DigMandarin to show you the proper stroke orders.

Here are some tips on mastering stroke order.

1). 从上到下Top to bottom

When a Chinese character is “stacked” vertically, like the character 立 (lì) which means to stand, the rule is to write from top to bottom.

2). 从左到右Left to right

When a Chinese character has a radical, the character is written left to right. The same rule applies to characters that are stacked horizontally.

3). 先中间后两边Symmetry counts

When you are writing a character that is centered and more or less symmetrical (but not stacked from top to bottom) the general rule is to write the center stroke first.

4). 先横后竖Horizontal first, vertical second

Horizontal strokes are always written before vertical strokes. Here is how to write the character “十(shí)” or “ten.”

5). Enclosures before content

You want to create the frame of the character before you fill it in. Check out how to write the character 日(rì) or “sun.”

6). Close frames last

Make a frame then fill in some of the components inside. After you write the middle strokes, close the frame, such as in the character “回(huí)” or “to return.”

7). Character spanning strokes are last

For strokes that cut across many other strokes, they are often written last. For example, the character 半 (bàn), which means “half.” The vertical line is written last.

There are always small exceptions to the rule, and Chinese stroke order can vary slightly from region to region. However, these variations are very miniscule; so by following these general tips, you’ll have an astute grasp on Chinese character`s writing order.

From strokes to characters, this is the way Chinese characters are formed. And it should also be the way you learn to write them. Writing is not the final goal, but understanding and using them correctly. Following the order of the writing will help you remember the characters better.

Conclusion

Arch Chinese is a premier Chinese learning system crafted by Chinese teachers in the United States for Mandarin Chinese language learners at K-12 schools and universities. It offers a rich set of features with a slick and easy-to-use user interface and is designed specifically for English speakers who have little to no knowledge of Mandarin Chinese.