How to Write Grants – Yes, grants are a thing. Grant applications have been a great tool for researchers before the creation of online academic publishing portals and billion-dollar scientific journals that gained prominence in the last two decades or so. In this article, we will talk about how to write a grant proposal.

Table of Contents

So what is a grant proposal?

In short, it’s a request for an investment in a non-profit or for-profit project. At first glance, grant proposals bear benefits only to the organization or individual entrepreneur who needs the money. But that’s not exactly true.

For Grantees (A Grantee is an individual or organization giving you the money), it’s not an investment in some random project but an investment in positive change. Thus, they can have a huge impact on issues that concern a company’s morals, values, or culture.

Before you start writing your grant proposal, you’ll want to make sure that you:

- develop a specific, meaningful, actionable plan for what you want to do and why you want to do it;

- consider how your plan will achieve positive results;

- locate a granting organization or source that funds projects like the one you have in mind;

- research that organization to make sure that its mission aligns with your plan;

- review the organization’s proposal guidelines; and

- examine sample proposals from your department, peers, and/or the organization.

When you’ve done all of this, you’re ready to start drafting your proposal!

Writing an effective grant proposal: the key steps

Before you start, you need to prepare. If we are talking about how to write a grant proposal for a non-profit organization, this document should be only a small part of your fundraising plan.

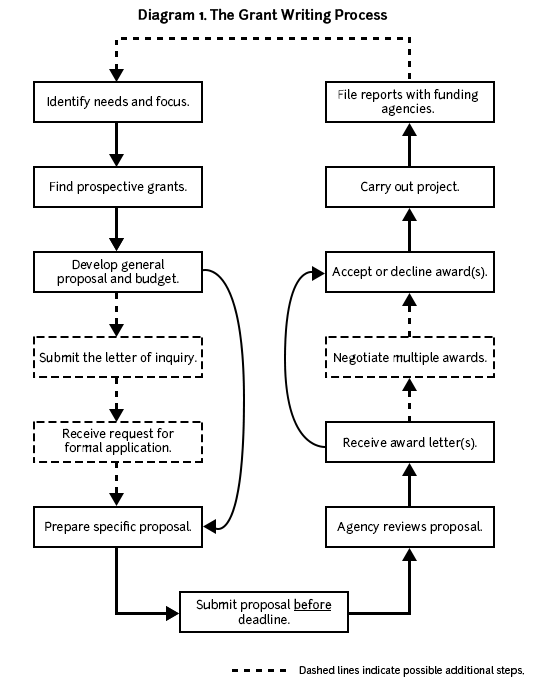

First, you need to define your fundraising goals, estimate the cost, develop the timeline of your project, and find prospective grants.

Almost the same applies to the process of “how to write a grant proposal for a small business”. In the United States, the new business should register in a federal grant program before they can ask for a grant.

It makes sense to submit a short grant letter before writing a full grant proposal to save you time.

If your Grantee approves your letter and sends you a request for a formal grant proposal, you can proceed with writing a detailed RFP response to this prospective investor.

To save even more time, you can use our document management software to assist you in this difficult task. Besides grant proposals, it can handle your quotes, agreements, contracts, and proposals.

Step 1. Write a strong cover letter

Your cover letter is the perfect opportunity to capture the funder’s attention and get your foot in the door. Unlike the rest of your grant application, the letter can be less formal and address the reader more directly.

The key objective of your cover letter is to compel the reader to get to your proposal. They’ve likely received tens or even hundreds of grant applications and your letter should separate you from the crowd as much as possible.

Here are some dos and don’ts when it comes to cover letters:

Do:

- Keep it short: Three to four paragraphs max. Get to the point quickly and state your intentions right away without too much fluff.

- Say what you need: At the very beginning, mention how much money you need and what for. Don’ be afraid to be direct — you deserve this grant so make sure the reader knows it.

- Avoid repeating yourself: This isn’t the place to just recap what you said in the proposal. Feel free to go a little off-course and provide something of value.

- Make a connection: Show that you understand the funder and draw a straight line from their mission and funds to your proposed project.

Don’t:

- Get too emotional: You shouldn’t write a heartfelt story about your mission or organization. Convey your message in a less formal manner but stay focused on your arguments.

- Mention your competition: No need to compare yourself with others. Just state your own desired outcome and try to make a good first impression without mentioning anyone else.

Here is how a good cover letter can start:

Dear Mr. Jones,

The Pet Care Clinic respectfully requests a grant of $30,000 for our South Boston Health Center Project.

As the largest independent pet hospital in Boston, we are aware of the challenges pet owners in our service area are faced with. We’re particularly concerned about the lack of service quality in South Boston given the fact that the area has the largest amount of pets per capita in the city.

We are committed to solving this issue by growing our community and providing our expertise to the people and animals of Boston by the end of 2021. The South Boston Health Center Project will allow us to provide access…

No fluff and right to the point!

Step 2. Start with a short executive summary

Moving onto grant writing: every winning grant needs to start with a brief executive summary.

Also known as a proposal summary, an executive summary is essentially a brief synopsis of the entire proposal. It introduces your business, market segment, proposal, project goals — essentially, your grant request.

It should have sufficient detail and specifics; get to the point quickly and be pragmatic and factual.

Do:

- Keep it up to two pages long: You need to provide just enough information that the grantee can read only this part and get a solid idea of who you are and what you need the money for.

- Include the resources: Mention the funds you’re requesting and briefly explain your methodology when it comes to spending them.

- Introduce your organization: Although you will go into detail about this later, don’t be afraid to tell the grantee about your history, mission, and objectives.

Don’t:

- Address the funder directly: The only place to do this is the cover letter. Now that we’ve started writing a grant application, things need to get more formal.

- Give out too much: Don’t go too deep into the project description, you will have space for this later.

So, here are some questions that a good grant writer will answer in their executive summary:

1. What is your mission and history? What do you do?

2. What is your project’s name and who is it supposed to help?

3. What problem are you solving and why should it matter?

4. What is your end goal and how will you measure whether you achieved it?

5. Why should you get the funds? What are your competencies?

6. How much money do you need and how do you plan to finance the project in the future? Do you have other funding sources?

Step 3. Introduce your organization

Now that you’ve set the stage for the entire proposal, you can start with your business/organization. Share as much relevant information as you can about your infrastructure, history, mission, experience, etc.

Here you include a biography of key staff, your business track record (success stories) company goals, and philosophy; essentially highlight your expertise.

Client recommendations, letters of thanks, feedback from customers and the general public are must-have things to write in a grant proposal.

Also include all valid industry certifications (ISO or Quality Certifications), licenses, and business and indemnity insurance details.

You need to show that your company or organization has the capacity and the ability to meet all deliverables from both an execution perspective but also meet all legal, safety, and quality obligations.

You may need to provide solvency statements to prove that you can meet your financial commitments to your staff and contractors.

Do:

- Be objective: It’s easy to start patting yourself on the back a little too much and try to convince the grant reviewers that you’re the best of the best. Try to avoid this trap and stay factual.

- Provide a backstory: When was the company/organization started and why? Try to connect your mission to that of the grantmaker as naturally as possible.

Don’t:

- Go into too much detail: You don’t need to list all of your employees by name. Provide biographies of key staff (like the executive director) and just mention your total number of employees.

- Stray from the point: This entire section should be formulated to make the point that you’re the best organization to get the funding, not anyone else. Don’t get too descriptive and forget about this fact.

Step 4. Write a direct problem statement

One of the most important parts of the grant proposal structure is the problem statement.

Also known as the “needs statement” or “statement of need“, this is the place where you explain why your community has a problem and how you can provide the solution.

You may need to do extensive research on the history of the underlying problem, previous solutions that were implemented and potentially failed, and explain why your solution will make a difference.

In a winning grant proposal, the problem statement will heavily rely on quantitative data and clearly display how your organization answers a need.

Do:

- Use comparable data: Rely on the results of other communities that already implemented your solution and got satisfactory outcomes.

- Highlight urgency: Underline that it’s essential this project is started now rather than later.

- Focus on the main problem: Try not to get sidetracked by other phenomena that are contributing to the key problem you’re addressing.

Don’t:

- Make it about you: It’s not your organization that needs the grant funding, it’s the community.

- Use circular reasoning: Don’t formulate the problem as “The city doesn’t have a youth center –> We can build a youth center”. Why does the city need a youth center in the first place? That should be the thought behind your writing process.

Here’s how a brief problem statement could look:

A 2017 report from [institution] showed that the town of [your community] has the highest [problem stat] per capita in the state of [your state]. Another study by [institution] confirmed these findings in 2020, highlighting the importance of [potential solution] in dealing with these issues.

There is a need for education and professional services in: [fields and industries] backed by expertise and a strong infrastructure.

To meet this need, [your organization] proposes a [your program] that would, for the first time, address the problem of [problem].

With PandaDoc, you get a free grant proposal template that has all of these sections incorporated!

Step 5. State your goals and objectives

Another important part of the grant proposal process is clearly stating your goals and objectives. In fact, a lot of proposals fail because they forget or mishandle this step so all their hard work goes to waste!

Write details about the desired outcome and how success will be measured. This section is key to providing information on the benefits that the grantee, community, government, or client will see for their investment.

And, although they sound similar, Goals and Objectives should be separated. Think of Goals as broad statements and Objectives as more specific statements of intention with measurable outcomes and a time frame.

Do:

- State objectives as outcomes: An objective is something you want to achieve, not do.

- Make your objectives SMART: You can’t really track your progress if your objectives aren’t SMART: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-bound.

- Connect goals and objectives to the audience: The final result of your project should always be the betterment of your community expressed in a measurable way.

Don’t:

- Be too ambitious: Make sure your goals are attainable and don’t get too ahead of yourself.

- Mistake goals for processes: Goals are always stated as results and measurable outcomes with a deadline, not as processes.

Here is an example of well-formulated goals and objectives.

Goal: Improve the literacy and overall ability of expression of children from inner-city schools in the [community].

Objective: By the end of the 2023 school year, improve the results of reading and writing tests for fourth-graders in the [community] by at least 20% compared to current results (55/100, on average).

Notice how the goal is more optimistic and abstract while the objective is more measurable and to the point.

Step 6. Project design: methods and strategies

Now that the funding agency or grantee knows your goals, it’s time to tell them how you plan on achieving them.

List the new hires and skills, additional facilities, transport, and support services you need to deliver the project and achieve the defined measures for success.

Good project management discipline and methodologies with detailed requirements specified and individual tasks articulated (project schedule) will keep a good focus on tasks, deliverables and results.

Do:

- Connect to the objectives: Your methods and strategies absolutely need to be connected to the objectives you outlined, as well as the needs statement.

- Provide examples: If you can, find examples of when these same methods worked for previous projects.

- Demonstrate cost-effectiveness: Make sure that the grantmaker realizes that your methods are rational, well-researched, and cost-effective.

Don’t:

- Assume things: Don’t approach the topics like the reader is well-versed in the field. Be specific and introduce your methodologies as though you’re talking to someone who knows nothing about your organization or propositions.

- Forget about your audience: You need to demonstrate that the particular strategies you chose make sense for the community.

Step 7. The evaluation section: tracking success

This section covers process evaluation — how will you track your program’s progress?

It also includes the timeframe needed for evaluation and who will do the evaluation including the specific skills or products needed and the cost of the evaluation phase of the project.

This is one of the most important steps to writing a grant proposal, as all funders will look for evaluations.

Whether we’re talking about government agencies or private foundations, they all need to know if the program they invested in made a difference.

Evaluation can be quite expensive and need to have entry and exit criteria and specifically focused in-scope activities. All out-of-scope evaluation activities need to be specified as this phase can easily blow out budget-wise.

Once again, solid project management discipline and methodologies will keep a good focus on evaluation tasks and results.

Do:

- Obtain feedback: However you imagine your evaluation process, it needs to include some sort of feedback from the community taking part in the project.

- Decide between internal and external evaluation: One of the most important variables here is whether you’ll be doing the evaluation with your staff or hire an external agency to do it independently.

Don’t:

- Be vague: You need to clearly outline the measurement methods that will tell both you and your funders how the program is doing. No room for vagueness here.

- Neglect time frames: It’s not just about measuring success, it’s about measuring success across time. So, make sure your evaluation strategies are periodic.

To go back to our child literacy example, here is how an evaluation would look for that project:

Project Evaluation

The program facilitators will administer both a set of pretests and posttests to students in order to determine to which degree the project is fulfilling the objectives. The periodic tests will be created by a set of outside collaborators (experts in child education) and will take place on a monthly basis for the duration of the program.

After each session, we will ask participating teachers to write a qualitative evaluation in order to identify areas of improvement and generate feedback […]

Step 8. Other funding sources and sustainability

Your founders won’t like the idea of investing in a short-term project that has no perspective. They’ll be much more willing to recognize a long-term winner and reward a promising project that can run on a larger scale.

That’s why you need to show how you can make this happen.

This section of your grant proposal is for funding requirements that go beyond the project, total cost of ownership including ongoing maintenance, daily business, and operational support.

This and may require you to articulate the projected ongoing costs (if any) for at least 5 years.

An accurate cost model needs to include all factors including inflation, specialist skills, ongoing training, potential future growth, and decommissioning expenses when the project or the product reaches the end of its life cycle.

Do:

- Have a strong blueprint: Most grant reviewers will know a thing or two about business plans so you need to show a viable blueprint for sustainability. Exactly how will you generate revenue and keep the project going?

- Mention other funding: If you plan to get more government funding, this is the place to mention it. Don’t think that this isn’t a good long-term strategy.

Don’t:

- Leave anything out: Don’t leave space for speculation or filling in the blanks. Everything needs to be outlined and you need to show — without a doubt — that your program can run even after the initial resources are gone.

Step 9. Outline a project budget

Of course, one of the most important grant proposal topics is budgeting. This is the moment when you go into detail about exactly how you’ll be using the resources from an operational standpoint.

Provide full justification for all expenses including a table of services (or service catalog) and product offered can be used to clearly and accurately specify the services.

Remember that the project budget section is the true meat of your grant proposal.

Overcharging or having a high quote can lose you the grant and even be seen as profiteering. Underquoting might win you the business but you may not be able to deliver on your proposal which could adversely impact your standing with the grantee.

Many grantors underquote in the hope of “hooking” in the reader and then looking for additional funding at a later stage.

This is a dangerous game to play and could affect your individual or company’s brand, community standing, or industry reputation.

Do:

- Pay attention to detail: Everything, and we mean everything needs to be covered. Travel costs, supplies, advertising, personnel — don’t leave anything out.

- Double-check: It can be easy to leave out a zero or move a decimal point and distort everything by accident. Be thorough!

- Round off your numbers: This is just for the readers’ sake. A lot of decimal points and uneven numbers will be harder to track.

Don’t:

- Do it alone: Especially if you’re not that good with numbers, don’t hesitate to include other people and assemble a team to tackle this task together.

- Forget about indirect costs: A lot of grant writers will leave out indirect costs like insurance, utilities, trash pickup, etc. These can stack up, so be careful not to forget them!

Considering the Audience, Purpose, and Expectations of a Grant Proposal

A grant proposal is a very clear, direct document written to a particular organization or funding agency with the purpose of persuading the reviewers to provide you with support because: (1) you have an important and fully considered plan to advance a valuable cause, and (2) you are responsible and capable of realizing that plan.

As you begin planning and drafting your grant proposal, ask yourself:

- Who is your audience?

Think about the people from the agency offering this grant who will read this proposal. What are the agency’s mission and goals? What are its values? How is what you want to do aligned with what this agency is all about? How much do these readers know about what you are interested in? Let your answers to these questions inform how you present your plan, what vocabulary you use, how much background you provide, and how you frame your goals. In considering your audience, you should think about the kind of information these readers will find to be the most persuasive. Is it numbers? If so, make sure that you provide and explain your data. Is it testimonials? Recommendations from other collaborators? Historical precedent? Think closely about how you construct your argument in relationship to your readers. - What are the particular expectations for this grant?

Pay attention to everything the granting organization requires of you. Your proposal should adhere exactly to these requirements. If you receive any advice that contradicts the expectations of your particular situation (including from this website), ignore it! Study representative samples of successful proposals in your field or proposals that have received the particular grant you are applying for. - How do you establish your credibility?

Make sure that you present yourself as capable, knowledgeable, and forward thinking. Establish your credibility through the thoroughness of your plan, the intentional way that you present its importance and value, and the knowledge you have of what has already been learned or studied. Appropriately reference any past accomplishments that verify your ability to succeed and your commitment to this project. Outline any partnerships you have built with complementary organizations and individuals. - How can you clearly and logically present your plan?

Make sure that your organization is logical. Divide your proposal into predictable sections and label them with clear headings. Follow exactly the headings and content requirements established by the granting agency’s call for proposals.Grant proposals are direct and to–the–point. This isn’t a good place for you to embroider your prose with flowery metaphors or weave in subtle literary allusions. Your language should be uncluttered and concise. Match the concepts and language your readers use and are familiar with. Your readers shouldn’t have to work hard to understand what you are communicating. For information about writing clear sentences, see this section of our writer’s handbook. However, use a vivid image, compelling anecdote, or memorable phrase if it conveys the urgency or importance of what you are proposing to do.

General Tips

Pay attention to the agency’s key interests.

As mentioned earlier, if there are keywords in the call for proposals—or in the funding organization’s mission or goal—be sure to use some of those terms throughout your proposal. But don’t be too heavy–handed. You want to help your readers understand the connections that exist between your project and their purpose without belaboring these connections.

Organize ideas through numbered lists.

Some grant writers use numbered lists to organize their ideas within their proposal. They set up these lists with phrases like, “This project’s three main goals are . . . ” or, “This plan will involve four stages . . . ” Using numbers in this way may not be eloquent, but it can an efficient way to present your information in a clear and skimmable manner.

Write carefully customized proposals.

Because grant funding is so competitive, you will likely be applying for several different grants from multiple funding agencies. But if you do this, make sure that you carefully design each proposal to respond to the different interests, expectations, and guidelines of each source. While you might scavenge parts of one proposal for another, never use the exact same proposal twice. Additionally when you apply to more than one source at the same time, be sure to think strategically about the kind of support you are asking from which organization. Do your research to find out, for example, which source is more likely to support a request for materials and which is more interested in covering the cost of personnel.

Go after grants of all sizes.

Pay attention to small grant opportunities as well as big grant opportunities. In fact, sometimes securing a smaller grant can make your appeal for a larger grant more attractive. Showing that one or two stakeholders have already supported your project can bolster your credibility.

Don’t give up! Keep on writing!

Writing a grant proposal is hard work. It requires you to closely analyze your vision and consider critically how your solution will effectively respond to a gap, problem, or deficiency. And often, even for seasoned grant writers, this process ends with rejection. But while grant writers don’t receive many of the grants they apply to, they find the process of carefully delineating and justifying their objectives and methods to be productive. Writing closely about your project helps you think about and assess it regardless of what the grant committee decides. And of course, if you do receive a grant, the writing won’t be over. Many grants require progress reports and updates, so be prepared to keep on writing!

Conclusion

How to write a grant proposal is a question that researchers often ask themselves. A grant proposal can be a large undertaking and require a lot of time, but it will be worth it. It is also common for beginning researchers to develop a grant proposal without assistance from a grant writing consultant or organization.