In this article we will write be talking about how to write better. In order to get a deeper idea of how to write better, you need to learn the basics of good writing.

Perhaps you have dreams of becoming the next Great Novelist. Or maybe you just want to be able to better express your thoughts and ideas more clearly. Whether you want to improve your writing skills as a creative writer or simply perfect your skills for schoolwork, you can take some steps to learn how to be a better writer. Becoming a great writer—or even a good writer—takes practice and knowledge, but with enough hard work perhaps someday somebody will aspire to be the next you!

Table of Contents

Method 1 Improving the Basics

Use active instead of passive voice. One of the most common manifestations of bad writing is overuse of the passive voice. In English, the most basic sentence structure is S-V-O: Subject-Verb-Object. “The zombie bit the man” is an example of this sentence structure. The passive voice can cause confusion by putting the object first: “The man was bitten by the zombie.” It usually requires more words and use of a “to be” verb form, which can suck the energy out of your writing. Learn to avoid these constructions as much as you can.

- Using the passive voice isn’t always bad. Sometimes there is no clear way to make a statement active, or sometimes you want the lighter touch a passive construction allows. But learn to follow this rule before you start making exceptions.

- The main exception to this is science writing, which conventionally uses the passive voice to put the emphasis on the results, rather than the researchers (although this is changing, so check the guidelines before you write). For example, “puppies fed spicy dog food were found to have more upset stomachs” puts the emphasis on the finding rather than the person doing the finding.

Use strong words. Good writing, whether it’s in a novel or a scholarly essay, is precise, evocative and spiced with the unexpected. Finding the right verb or adjective can turn an uninspired sentence into one people will remember and quote for years to come. Look for words that are as specific as possible. Try not to repeat the same word over and over unless you are trying to build a rhythm with it.

- One exception to this is the words used to describe dialogue. Bad writing is filled with “he commented” and “she opined.” A well-placed “sputtered” can work wonders, but most of the time a simple “said” will do. It may feel awkward to use the word “said” over and over, but changing it up unnecessarily makes it harder for your readers to get into the back-and-forth flow of the conversation. “He said/she said” becomes nearly invisible to your readers after a while, allowing them to stay focused on the characters’ voices.

- Strong doesn’t mean obscure, or more complicated. Don’t say “utilize” when you could say “use.” “He sprinted” is not necessarily better than “he ran.” If you have a really good opportunity to use “ameliorate,” go for it—unless “ease” is just as good there.

- Thesauruses can be handy, but use them with caution. Consider the predicament Joey from Friends gets into when he uses a thesaurus without also consulting a dictionary: “They’re warm, nice people with big hearts” becomes “They’re humid, prepossessing homo sapiens with full-sized aortic pumps.” If you’re going to use a thesaurus to spice up your vocabulary, look up your new words in the dictionary to determine their precise meaning.

Cut the chaff. Good writing is simple, clear and direct. You don’t get points for saying in 50 words what could be said in 20, or for using multi-syllable words when a short one does just as well. Good writing is about using the right words, not filling up the page. It might feel good at first to pack a lot of ideas and details into a single sentence, but chances are that sentence is just going to be hard to read. If a phrase doesn’t add anything valuable, just cut it.

- Adverbs are the classic crutch of mediocre writing, and they often serve only to clutter up a sentence. A well-placed adverb can be delightful, but much of the time the adverbs we use are already implied by the verb or adjective—or would be if we had chosen a more evocative word. Don’t write “screamed fearfully” — “scream” already suggests fear. If you notice that your writing is filled with “-ly” words, it might be time to take a deep breath and give your writing more focus.

- Sometimes cutting the chaff is best done at the editing stage. You don’t have to obsess about finding the most concise way to phrase every sentence; get your ideas down on paper however you can and then go through to edit out unnecessary stuff.

- Your writing doesn’t just exist in a vacuum—it’s experienced in conjunction with the reader’s imagination. You don’t need to describe every detail if a few good ones can spur the reader’s mind to fill in the rest. Lay down well-placed dots and let the reader connect them.

Show, don’t tell. Don’t tell your readers anything that could be shown instead. Instead of just sitting your readers down for a long exposition explaining a character’s background or a plot-point’s significance, try to let the readers discover the same ideas through the words, feelings and actions of your characters. Especially in fiction, putting this classic piece of writing advice into practice is one of the most powerful lessons a writer can learn

- For example, “Sydney was angry after reading the letter” tells the reader that Sydney felt angry, but doesn’t give us any way to see it for ourselves. It’s lazy and unconvincing. “Sydney crumpled the letter and threw it into the fireplace before she stormed from the room” shows that Sydney was angry without having to say it outright. This is far more effective. Readers believe what we see, not what we’re told.

Avoid clichés. Clichés are phrases, ideas or situations that have been used so often that they’ve lost any impact they once had. They’re also usually too general to leave a lasting impression on your reader. Whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction, cutting clichés out of your work will make it better.

- “It was a dark and stormy night” is a classic example of a clichéd phrase—even now a clichéd concept. Compare these similar weather-related opening lines:

- “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”—1984, by George Orwell. It’s not dark, nor stormy, nor night. But you can tell right from the start something’s not quite right in 1984.

- “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.”—Neuromancer, by William Gibson, in the same book that gave us the word “cyberspace.” This not only gives you the weather report, it does so in such a way that you are immediately placed into his dystopian world.

- ““It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”—A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens. Weather, emotion, damnation, and despair—Dickens covered it all with an opening line that leaves the reader ready for anything.

- Clichés are also important to avoid when you’re writing about yourself. Saying you’re a “people person” says nothing definite about you. Saying you’re able to communicate well with a variety of people because you grew up in a bilingual family and lived in six countries growing up lets your reader know you’re a “people person” without you relying on lazy language.

Avoid generalizations. One of the hallmarks of sloppy writing is broad generalizations. For example, an academic essay might say something like “In modern times, we are more progressive than people a hundred years ago.” This statement makes a host of unfounded assumptions and doesn’t define important ideas like “progressive.” Be precise and specific. Whether you’re writing a short story or a scholarly essay, steering clear of generalizations and universal statements will improve your writing.

- This applies to creative writing, too. Don’t allow yourself to assume anything without examining it. For example, if you’re writing a story about a female character, don’t assume that she would automatically be more emotional than a man or more inclined to be gentle or kindly. This kind of non-examined thinking keeps you in a creative rut and prevents you from exploring the variety of possibilities that real life presents.

Back up what you say. Don’t speculate without providing evidence for your assertions. In creative writing terms, this is similar to the “show, don’t tell” principle. Don’t just say that without a strong police force society as we know it would break down. Why is that true? What evidence do you have? Explaining the thinking behind your statements will allow readers to see that you know what you’re talking about. It will also help them determine whether they agree with you.

Use metaphors and similes with caution. While a good metaphor or simile can give your writing punch and vigor, a bad one can make your writing as weak as a baby. (That, by the way, was a weak simile.) Overusing metaphors and similes can also suggest that you aren’t confident with what you’re saying and are relying on figures of speech to explain your ideas. They can also become clichéd really quickly.

- A “mixed” metaphor mixes two metaphors so that they don’t make sense. For example, “We’ll burn that bridge when we come to it” mixes the common metaphor “We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it” and “Don’t burn bridges.” If you’re not sure how a metaphor goes, look it up — or skip it altogether.

Break the rules. The best writers don’t just follow the rules—they know when and how to break them. Everything from traditional grammar to the writing advice above is up for grabs if you know a transgression will improve your piece. The key is that you have to write well enough the rest of the time that it’s clear you are breaking the rule knowingly and on purpose.

- As with everything, moderation is key. Using one rhetorical question to create a punchy opening can be very effective. Using a string of six rhetorical questions would quickly diminish their effect. Be choosy about when and why you break the rules.

Edit, edit, edit. Editing is one of the most essential parts of writing. Once you finish a piece of writing, let it sit for a day and then read it over with fresh eyes, catching confusing bits or scrapping whole paragraphs—anything to make your piece better. Then when you are done, give it another read, and another.

- Some people confuse “editing” with “proofreading.” Both are important, but editing focuses on considering what your content is and how it works. Don’t become so attached to your wording or a particular idea that you aren’t willing to change it if you discover that your ideas would be more clear or effective presented in another way. Proofreading is more technical and catches errors of grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting.

Method 2 Reading for Writing

Pick up a good book or ten. Whether you’re writing the next Great American Novel or a scientific journal article, becoming familiar with examples of excellent writing in your genre will help you improve your own writing. Read and understand the works of great and influential writers to learn what is possible with the written word and what readers respond to best. By immersing yourself in works by good writers, you will expand your vocabulary, build knowledge, and feed your imagination.

- Look for different ways of organizing a piece of writing or presenting a narrative.

- Try comparing different author’s approaches to the same subject to see how they are alike and how they differ. For example, Tolstoy’s Death of Ivan Ilych, and Hemingway’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

- Remember that even if you’re writing nonfiction or academic writing, reading examples of great writing will improve your own. The more familiar you are with the many ways it’s possible to communicate ideas, the more varied and original your own writing can become.

Map the allusions that run through your culture. You might not realize it, but books, movies and other media are filled with references and homages to great literature. By reading some classics, you will build a body of cultural knowledge that will better inform your own writing.

Make sure you understand why a classic work is considered great. It’s possible to read a novel like The Catcher in the Rye and not “get it” or see its value immediately. If this happens, try reading an essay or two about the piece to learn why it was so influential and effective. You may discover layers of meaning that you missed. Understanding what makes great writing great is one of the best ways to grow your own skills.

- This applies for nonfiction and academic writing too. Take some examples of work by well-respected authors in your field and take them apart. What do they have in common? How do they work? What are they doing that you could do yourself?

Attend the theatre. Plays were written to be performed. If you find that you just don’t “get” a work of literature, find a performance of it. If you can’t find a performance, read the work aloud. Get yourself into the heads of its characters. Listen to how the language sounds as you read it.

- More than a movie ever can be, a theatrical performance is like words come to life, with only the director’s interpretation and the actor’s delivery as filters between the author’s pen and your ears.

Read magazines, newspapers, and everything else. Literature isn’t the only place to get ideas—the real world is filled with fascinating people, places and events that will inspire your writerly mind. A great writer is in touch with the important issues of the day.

Know when to put down your influences. It happens all the time: you finish an awesome novel, and it leaves you fired up to get cracking on your own writing. But when you sit down at your desk, your words come out sounding unoriginal, like an imitation of the author you were just reading. For all you can learn from great writers, you need to be able to develop your own voice. Learn to cleanse your palate of influences with a free writing exercise, a review of your past works, or even just a meditative jog.

Method 3 Practicing Your Skills

Buy a notebook. Not just any notebook, but a good sturdy one you can take with you anywhere. Ideas happen anywhere, and you want to be able to capture those oft-fleeting ideas before they escape you like that dream you had the other night about…um…it was…uh…well it was really good at the time!

Write down any ideas that come to you. Titles, subtitles, topics, characters, situations, phrases, metaphors—write down anything that will spark your imagination later when you’re ready.

- If you don’t feel creatively inspired, practice taking notes about situations. Write down the way people work at a coffee shop. Note how the sunlight strikes your desk in the late afternoon. Paying attention to concrete details will help you be a better writer, whether you’re writing poetry or a newspaper article.

Fill up your notebook and keep going. When you finish a notebook, put a label on it with the date range and any general notes, so you can refer back to it when you need a creative kick in the pants.

Join a writing workshop. One of the best ways to improve your writing and stay motivated is to talk with others and get feedback on your work. Find a local or online writing group. In these groups members usually read each other’s writing and discuss what they liked, didn’t like and how a piece might be improved. You may find that offering feedback, as well as receiving it, helps you learn valuable lessons to build your skills.

- Workshops aren’t just for creative writers! Academic writing can also be improved by having friends or colleagues look at it. Working with others also encourages you to share your ideas with others and listen to theirs.

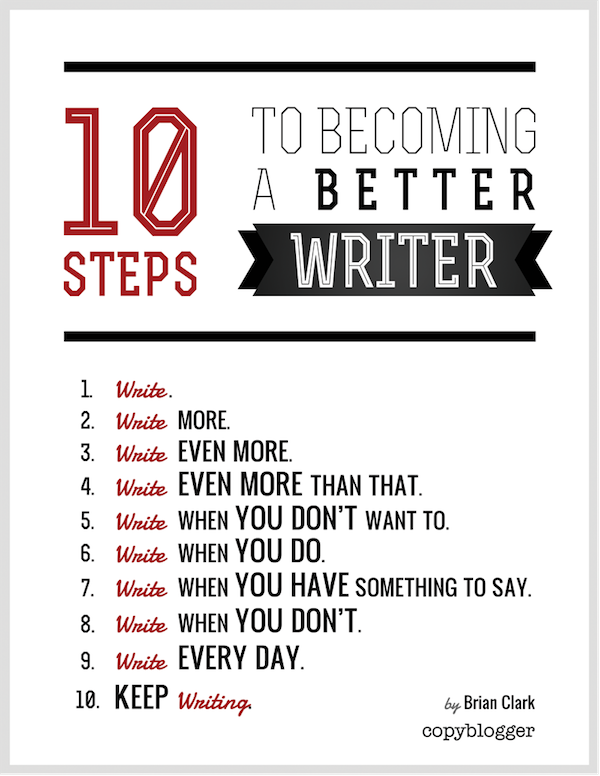

Write every day. Keep a diary, mail a pen pal, or just set aside an hour or so for free writing. Just pick a topic and start writing. The topic itself doesn’t matter—the idea is to write. And write. And write some more. Writing is a skill that takes practice, and it’s a muscle that you can strengthen and nourish with the right training.

Method 4 Crafting a Story

Pick a topic and lay out a general arc for your story. It doesn’t have to be complex, just a way to get your head around the direction of the plot. For example, that classic Hollywood story line: boy meets girl, boy gets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back again. (The chase scenes are added later.)

Write an outline. It can be tempting to just start writing and try to figure out twists and turns of your plot as you go along. Don’t do it! Even a simple outline will help you see the big picture and save you hours of rewriting. Start with a basic arc and expand section by section. Flesh out your story, populating it with at least the main characters, locations, time period, and mood.

- When you have part of an outline that will take more than a few words to describe, create a sub-outline to break that section into manageable parts.

Keep some space in your story outline to add characters, and what makes them who they are. Give each of them a little story of their own, and even if you don’t add that info into your story, it will give a sense of how your character might act in a given situation.

Don’t be afraid to hop around. If you suddenly have a brilliant idea about how to resolve a situation near the end, but you’re still on Chapter 1, write it down! Never let an idea go to waste.

Write the first draft. You’re now ready to start your “sloppy copy,” otherwise known as your first draft! Using your outline, flesh out the characters and the narrative.

- Don’t let yourself get bogged down here. It’s not crucial to find exactly the perfect word when you’re drafting. It’s much more important to get all your ideas out so you can tinker with them.

Let your story guide you. Let your story have its say, and you may find yourself heading in unexpected, but very interesting directions. You’re still the director, but stay open to inspiration.

- You’ll find that if you’ve thought sufficiently about who your characters are, what they want, and why they want it, they’ll guide how you write.

Finish your first draft. Don’t get caught up in fine tuning things yet, just let the story play out on paper. If you realize 2/3 of the way through the story that a character is really the Ambassador to India, make a note, and finish the story with her as the Ambassador. Don’t go back and start re-writing her part till you’re done with the first draft.

Write it again. First draft, remember? Now you get to write it from the beginning, this time knowing all the details of your story that will make your characters much more real and believable. Now you know why he’s on that airplane, and why she is dressed like a punk.

Write it through to the end. By the time you are done with the second draft, you will have all the information about your story, your characters, the main plot, and the subplots defined.

Read and share your story. Now that you’ve finished the second draft, it’s time to read it—dispassionately, if possible, so that you can at least try to be objective. Share it with a couple trusted friends whose opinions you respect.

Write the final draft. Armed with notes from your reading the story, plus notes of your friends or publishers, go through your story one more time, finalizing as you go. Tie up loose ends, resolve conflicts, eliminate any characters that do not add to the story.

Conclusion

To become a better writer, you must learn how to write better. The more you read and write, the more your skill as a writer will improve. As a result, writers who don’t know how to write better will never enjoy the fruits of their labour.