How to Write User Stories – User stories can be a great way of breaking down a feature into tangible, testable pieces – providing a bridge between the users and the developers. But there’s more to them than just user stories examples. In this article, I want to explain how it works, what a good acceptance criteria is, and a bunch more features and user stories examples.

A user story is an informal, general explanation of a software feature written from the perspective of the end user. Its purpose is to articulate how a software feature will provide value to the customer.

It’s tempting to think that user stories are, simply put, software system requirements. But they’re not.

A key component of agile software development is putting people first, and a user story puts end users at the center of the conversation. These stories use non-technical language to provide context for the development team and their efforts. After reading a user story, the team knows why they are building, what they’re building, and what value it creates.

User stories are one of the core components of an agile program. They help provide a user-focused framework for daily work — which drives collaboration, creativity, and a better product overall.

Table of Contents

What are agile user stories?

A user story is the smallest unit of work in an agile framework. It’s an end goal, not a feature, expressed from the software user’s perspective.

A user story is an informal, general explanation of a software feature written from the perspective of the end user or customer.

The purpose of a user story is to articulate how a piece of work will deliver a particular value back to the customer. Note that “customers” don’t have to be external end users in the traditional sense, they can also be internal customers or colleagues within your organization who depend on your team.

User stories are a few sentences in simple language that outline the desired outcome. They don’t go into detail. Requirements are added later, once agreed upon by the team.

Stories fit neatly into agile frameworks like scrum and kanban. In scrum, user stories are added to sprints and “burned down” over the duration of the sprint. Kanban teams pull user stories into their backlog and run them through their workflow. It’s this work on user stories that help scrum teams get better at estimation and sprint planning, leading to more accurate forecasting and greater agility. Thanks to stories, kanban teams learn how to manage work-in-progress (WIP) and can further refine their workflows.

User stories are also the building blocks of larger agile frameworks like epics and initiatives. Epics are large work items broken down into a set of stories, and multiple epics comprise an initiative. These larger structures ensure that the day-to-day work of the development team (on stores) contributes to the organizational goals built into epics and initiatives.

Why create user stories?

For development teams new to agile, user stories sometimes seem like an added step. Why not just break the big project (the epic) into a series of steps and get on with it? But stories give the team important context and associate tasks with the value those tasks bring.

User stories serve a number of key benefits:

- Stories keep the focus on the user. A to-do list keeps the team focused on tasks that need to be checked off, but a collection of stories keeps the team focused on solving problems for real users.

- Stories enable collaboration. With the end goal defined, the team can work together to decide how best to serve the user and meet that goal.

- Stories drive creative solutions. Stories encourage the team to think critically and creatively about how to best solve for an end goal.

- Stories create momentum. With each passing story, the development team enjoys a small challenge and a small win, driving momentum.

How to write user stories

Consider the following when writing user stories:

- Definition of “done” — The story is generally “done” when the user can complete the outlined task, but make sure to define what that is.

- Outline subtasks or tasks — Decide which specific steps need to be completed and who is responsible for each of them.

- User personas — For whom? If there are multiple end users, consider making multiple stories.

- Ordered Steps — Write a story for each step in a larger process.

- Listen to feedback — Talk to your users and capture the problem or need in their words. No need to guess at stories when you can source them from your customers.

- Time — Time is a touchy subject. Many development teams avoid discussions of time altogether, relying instead on their estimation frameworks. Since stories should be completable in one sprint, stories that might take weeks or months to complete should be broken up into smaller stories or should be considered their own epic.

Once the user stories are clearly defined, make sure they are visible for the entire team.

tips

1 Users Come First

As its name suggests, a user story describes how a customer or user employs the product; it is told from the user’s perspective. What’s more, user stories are particularly helpful to capture a specific functionality, such as, searching for a product or making a booking. The following picture illustrates the relationship between the user, the story, and the product functionality (symbolised by the circle).

If you don’t know who the users and customers are and why they would want to use the product, then you should not write any user stories. Carry out the necessary user research first, for example, by observing and interviewing users. Otherwise, you take the risk of writing speculative stories that are based on beliefs and ideas—but not on data and empirical evidence.

2 Use Personas to Discover the Right Stories

A great technique to capture your insights about the users and customers is working with personas. Personas are fictional characters that are based on first-hand knowledge of the target group. They usually consist of a name and a picture; relevant characteristics, behaviours, and attitudes; and a goal. The goal is the benefit the persona wants to achieve, or the problem the character wants to see solved by using the product.

But there is more to it: The persona goals help you discover the right stories: Ask yourself what functionality the product should provide to meet the goals of the personas, as I explain in my post From Personas to User Stories. You can download a handy template to describe your personas from romanpichler.com/tools/persona-template.

3 Create Stories Collaboratively

User stories are intended as a lightweight technique that allows you to move fast. They are not a specification, but a collaboration tool. Stories should never be handed off to a development team. Instead, they should be embedded in a conversation: The product owner and the team should discuss the stories together. This allows you to capture only the minimum amount of information, reduce overhead, and accelerate delivery.

You can take this approach further and write stories collaboratively as part of your product backlog grooming process. This leverages the creativity and the knowledge of the team and results in better user stories.

If you can’t involve the development team in the user story work, then you should consider using another, more formal technique to capture the product functionality, such as, use cases.

4 Keep your Stories Simple and Concise

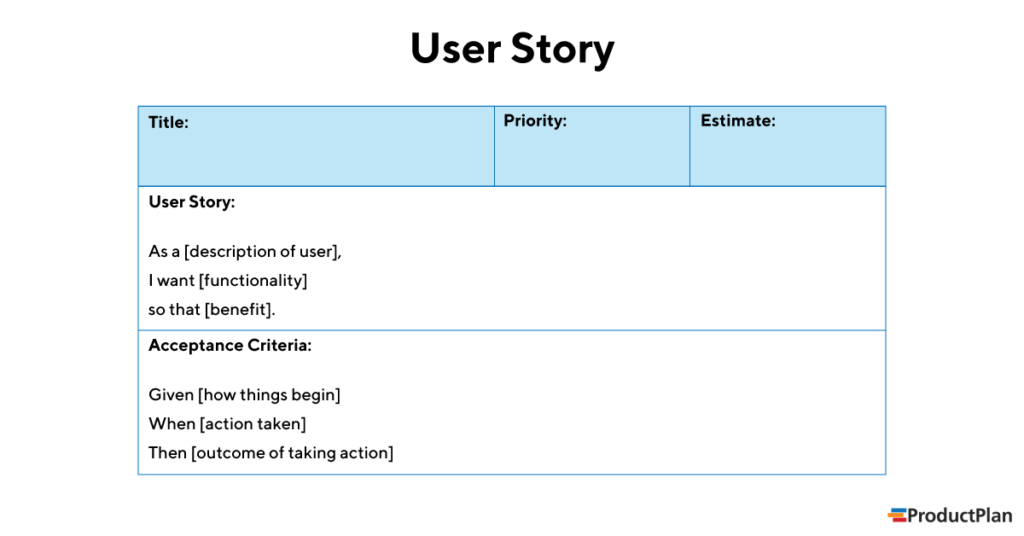

Write your stories so that they are easy to understand. Keep them simple and concise. Avoid confusing and ambiguous terms, and use active voice. Focus on what’s important, and leave out the rest. The template below puts the user or customer modelled as a persona into the story and makes its benefit explicit. It is based on by Rachel Davies’ popular template, but I have replaced user role with persona name to connect the story with the relevant persona.

As <persona> ,

I want <what?>

so that <why?>.

Use the template when it is helpful, but don’t feel obliged to always apply it. Experiment with different ways to write your stories to understand what works best for you and your team.

5 Start with Epics

An epic is a big, sketchy, coarse-grained story. It is typically broken into several user stories over time—leveraging the user feedback on early prototypes and product increments. You can think of it as a headline and a placeholder for more detailed stories.

Starting with epics allows you to sketch the product functionality without committing to the details. This is particularly helpful for describing new products and features: It allows you to capture the rough scope, and it buys you time to learn more about how to best address the needs of the users.

It also reduces the time and effort required to integrate new insights. If you have many detailed stories in the product backlog, then it’s often tricky and time-consuming to relate feedback to the appropriate items and it carries the risk of introducing inconsistencies.

6 Refine the Stories until They are Ready

Break your epics into smaller, detailed stories until they are ready: clear, feasible, and testable. All development team members should have a shared understanding of the story’s meaning; the story should not be too big and comfortably fit into a sprint; and there has to be an effective way to determine if the story is done.

7 Add Acceptance Criteria

As you break epics into smaller stories, remember to add acceptance criteria. Acceptance criteria complement the narrative: They allow you to describe the conditions that have to be fulfilled so that the story is done. The criteria enrich the story, they make it testable, and they ensures that the story can be demoed or released to the users and other stakeholders. As a rule of thumb, I like to use three to five acceptance criteria for detailed stories.

8 Use Paper Card

User stories emerged in Extreme Programming (XP), and the early XP literature talks about story cards rather than user stories. There is a simple reason: User stories were captured on paper cards. This approach provides three benefits: First, paper cards are cheap and easy to use. Second, they facilitate collaboration: Every one can take a card and jot down an idea. Third, cards can be easily grouped on the table or wall to check for consistency and completeness and to visualise dependencies. Even if your stories are stored electronically, it is worthwhile to use paper cards when you write new stories.

9 Keep your Stories Visible and Accessible

Stories want to communicate information. Therefore don’t hide them on a network drive, the corporate intranet jungle, or a licensed tool. Make them visible, for instance, by putting them up on the wall. This fosters collaboration, creates transparency, and makes it obvious when you add too many stories too quickly, as you will start running out of wall space. A handy tool to discover, visualise, and manage your stories is my Product Canvas shown below.

10 Don’t Solely Rely on User Stories

Creating a great user experience (UX) requires more than user stories. User stories are helpful to capture product functionality, but they are not well suited to describe the user journeys and the visual design. Therefore complement user stories with other techniques, such as, story maps, workflow diagrams, storyboards, sketches, and mockups.

Additionally, user stories are not good capturing technical requirements. If you need to communicate what an architectural element like a component or service should do, then write technical stories or—which is my preference—use a modeling language like UML.

Conclusion

Creating an Epic and a big User Story that contains several functions and Story points might be your trickshot. It will provide general guidance, and later you can divide it with the team into smaller User Stories that are closely linked to programming and development itself.