How to Write Poetry for Beginners – Follow these steps to write poetry you can be proud of. In this article, I will give you easy steps to writing perfect poetry for beginners. If you’re new to poetry, keep in mind there are no set rules you must follow. This is a guide to help you start your journey into the world of poetry.

Poetry, for many, is the art of writing in metered verse. Metered means having established rhythms or patterns of stresses or accents. I’m not going to get too scientific here, but take a look at John Keats’ Lines On A Grecian Urn for an example of quantitative verse. It would be impossible to write a sonnet without taking into account the rules that make poetry work in the first place. Today poetry exists in all forms. Anything you choose to write can be poetry!

Table of Contents

Starting the Poem

- Do writing exercises. A poem might start as a snippet of a verse, a line or two that seems to come out of nowhere, or an image you cannot get out of your head. You can find inspiration for your poem by doing writing exercises and using the world around you. Once you have inspiration, you can then shape and mould your thoughts into a poem.[1] Brainstorming for Ideas

Try a free write. Grab a notebook or your computer and just start writing—about your day, your feelings, or how you don’t know what to write about. Let your mind wander for 5-10 minutes and see what you can come up with.

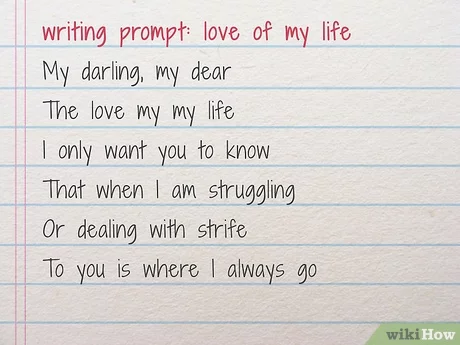

Write to a prompt. Look up poem prompts online or come up with your own, like “what water feels like” or “how it feels to get bad news.” Write down whatever comes to mind and see where it takes you.

Make a list or mind map of images. Think about a situation that’s full of emotion for you and write down a list of images or ideas that you associate with it. You could also write about something you see right in front of you, or take a walk and note down things you see. - Get inspired by your environment and those close to you. Inspiration for a great poem is all around you, even if you don’t see it just yet. Think of every memory, situation and moment as a possible topic and you’ll start seeing poetry all around you! Finding a Topic

Go for a walk. Head to your favorite park or spot in the city, or just take a walk through your neighborhood. Use the people you see and nature and buildings you pass as inspiration for a poem.

Write about someone you care about. Think about someone who’s really important to you, like a parent or your best friend. Recall a special moment you shared with them and use it to form a poem that shows that you care about them.

Pick a memory you have strong feelings about. Close your eyes, clear your head, and see what memories come to the forefront of your mind. Pay attention to what emotions they bring up for you—positive or negative—and probe into those. Strong emotional moments make for beautiful, interesting poems. - Pick a specific theme or idea. You can start your poem by focusing on a specific theme or idea that you find fascinating. Picking a specific theme or idea to focus on in the poem can give your poem a clear goal or objective. This can make it easier for you to narrow down what images and descriptions you are going to use in your poem. [2]

- For example, you may decide to write a poem around the theme of “love and friendship.” You may then think about specific moments in your life where you experienced love and friendship as well as how you would characterize love and friendship based on your relationships with others.

- Try to be specific when you choose a theme or idea, as this can help your poem feel less vague or unclear. For example, rather than choosing the general theme of “loss,” you may choose the more specific theme, such as “loss of a child” or “loss of a best friend.”

- Choose a poetic form. Get your creative juices flowing by picking a form for your poem. There are many different poetic forms that you can use, from free verse to sonnet to rhyming couplet. You may go for a poetic form that you find easy to use, such as free verse, or a form that you find more challenging, such as a sonnet. Choose one poetic form and stick to that structure so your poem feels cohesive to your reader.[3]

- You may decide to try a poetic form that is short, such as the haiku, the cinquain, or the shape poem. You could then play around with the poetic form and have fun with the challenges of a particular form. Try rearranging words to make your poem sound interesting.

- You may opt for a form that is more funny and playful, such as the limerick form, if you are trying to write a funny poem. Or you may go for a more lyrical form like the sonnet, the ballad, or the rhyming couplet for a poem that is more dramatic and romantic.

- Read examples of poetry. To get a better sense of what other poets are writing, you may look through examples of poetry. You may read poems written in the same poetic form you are interested in or poems about themes or ideas that you find inspiring. You may also choose poems that are well known and considered “classics” to get a better sense of the genre. For example, you may read:

Part 2 Writing the Poem

- Use concrete imagery. Avoid abstract imagery and go for concrete descriptions of people, places, and things in your poem. You should always try to describe something using the five senses: smell, taste, touch, sight, and sound. Using concrete imagery will immerse your reader in the world of your poem and make images come alive for them.[11]

- For example, rather than try to describe a feeling or image with abstract words, use concrete words instead. Rather than write, “I felt happy,” you may use concrete words to create a concrete image, such as, “My smile lit up the room like wildfire.”

- Include literary devices. Literary devices like metaphor and simile add variety and depth to your poetry. Using these devices can make your poem stand out to your reader and allow you to paint a detailed picture for your reader. Try to use literary devices throughout your poem, varying them so you do not use only metaphors or only similes in your writing.[12] Try a New Literary Device

Metaphor: This device compares one thing to another in a surprising way. A metaphor is a great way to add unique imagery and create an interesting tone. Example: “I was a bird on a wire, trying not to look down.”

Simile: Similes compare two things using “like” or “as.” They might seem interchangeable with metaphors, but both create a different flow and rhythm you can play with. Example: “She was as alone as a crow in a field,” or “My heart is like an empty stage.”

Personification: If you personify an object or idea, you’re describing it by using human qualities or attributes. This can clear up abstract ideas or images that are hard to visualize. Example: “The wind breathed in the night.”

Alliteration: Alliteration occurs when you use words in quick succession that begin with the same letter. This is a great tool if you want to play with the way your poem sounds. Example: “Lucy let her luck linger.” - Write for the ear. Poetry is made to be read out loud and you should write your poem with a focus on how it sounds on the page. Writing for the ear will allow you to play with the structure of your poem and your word choice. Notice how each line of your poem flows into one another and how placing one word next to another creates a certain sound [13]

- For example, you may notice how the word “glow” sounds compared to the word “glitter.” “Glow” has an “ow” sound, which conjures an image of warmth and softness to the listener. The word “glitter” is two syllables and has a more pronounced “tt” sound. This word creates a sharper, more rhythmic sound for the listener.

- Avoid cliche. Your poetry will be much stronger if you avoid cliches, which are phrases that have become so familiar they have lost their meaning. Go for creative descriptions and images in your poem so your reader is surprised and intrigued by your writing. If you feel a certain phrase or image will be too familiar to your reader, replace it with a more unique phrase.[14]

- For example, you may notice you have used the cliche, “she was as busy as a bee” to describe a person in your poem. You may replace this cliche with a more unique phrase, such as “her hands were always occupied” or “she moved through the kitchen at a frantic pace.”

Part 3 Polishing the Poem

- Read the poem out loud. Once you have completed a draft of the poem, you should read it aloud to yourself. Notice how the words sound on the page. Pay attention to how each line of your poem flows into the next. Keep a pen close by so you can mark any lines or words that sound awkward or jumbled. [15]

- You may also read the poem out loud to others, such as friends, family, or a partner. Have them respond to the poem on the initial listen and notice if they seem confused or unclear about certain phrases or lines.

- Get feedback from others. You can also share your poem with other poets to get feedback from them and improve your poem. You may join a poetry writing group, where you workshop your poems with other poets and work on your poetry together. Or you may take a poetry writing class where you work with an instructor and other aspiring poets to improve your writing. You can then take the feedback you receive from your peers and use it in your revision of the poem.[16]

- Revise your poem. Once you have received feedback on your poem, you should revise it until it is at its best. Use feedback from others to cut out any lines to feel confusing or unclear. Be willing to “kill your darlings” and not hold onto pretty lines just for the sake of including them in the poem. Make sure every line of the poem contributes to the overall goal, theme, or idea of the poem. [17]

- You may go over the poem with a fine-tooth comb and remove any cliches or familiar phrases. You should also make sure spelling and grammar in the poem are correct.

11 Rules for Poetry Writing Beginners

There are no officially sanctioned rules of poetry. However, as with all creative writing, having some degree of structure can help you reign in your ideas and work productively. Here are some guidelines for those looking to take their poetry writing to the next level. Or, if you literally haven’t written a single poem since high school, you can think of this as a beginner’s guide that will teach you the basics and have you writing poetry in no time.

- Read a lot of poetry. If you want to write poetry, start by reading poetry. You can do this in a casual way by letting the words of your favorite poems wash over you without necessarily digging for deeper meaning. Or you can delve into analysis. Dissect an allegory in a Robert Frost verse. Ponder the underlying meaning of an Edward Hirsch poem. Retrieving the symbolism in Emily Dickinson’s work. Do a line-by-line analysis of a William Shakespeare sonnet. Simply let the individual words of a Walt Whitman elegy flow with emotion.

- Listen to live poetry recitations. The experience of consuming poetry does not have to be an academic exercise in cataloging poetic devices like alliteration and metonymy. It can be musical—such as when you attend a poetry slam for the first time and hear the snappy consonants of a poem out loud. Many bookstores and coffeehouses have poetry readings, and these can be both fun and instructive for aspiring poets. By listening to the sounds of good poetry, you discover the beauty of its construction—the mix of stressed syllables and unstressed syllables, alliteration and assonance, a well placed internal rhyme, clever line breaks, and more. You’ll never think of the artform the same way once you hear good poems read aloud. (And if you ever get the chance to hear your own poem read aloud by someone else, seize the opportunity.)

- Start small. A short poem like a haiku or a simple rhyming poem might be more attainable than diving into a narrative epic. A simple rhyming poem can be a non-intimidating entryway to poetry writing. Don’t mistake quantity for quality; a pristine seven-line free verse poem is more impressive than a sloppy, rambling epic of blank verse iambic pentameter, even though it probably took far less time to compose.

- Don’t obsess over your first line. If you don’t feel you have exactly the right words to open your poem, don’t give up there. Keep writing and come back to the first line when you’re ready. The opening line is just one component of an overall piece of art. Don’t give it more outsized importance than it needs (which is a common mistake among first time poets).

- Embrace tools. If a thesaurus or a rhyming dictionary will help you complete a poem, use it. You’d be surprised how many professional writers also make use of these tools. Just be sure you understand the true meaning of the words you insert into your poem. Some synonyms listed in a thesaurus will deviate from the meaning you wish to convey.

- Enhance the poetic form with literary devices. Like any form of writing, poetry is enhanced by literary devices. Develop your poetry writing skills by inserting metaphor, allegory, synecdoche, metonymy, imagery, and other literary devices into your poems. This can be relatively easy in an unrhymed form like free verse and more challenging in poetic forms that have strict rules about meter and rhyme scheme.

- Try telling a story with your poem. Many of the ideas you might express in a novel, a short story, or an essay can come out in a poem. A narrative poem like “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot can be as long as a novella. “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe expresses just as much dread and menace as some horror movies. As with all forms of English language writing, communication is the name of the game in poetry, so if you want to tell short stories in your poems, embrace that instinct.

- Express big ideas. A lyric poem like “Banish Air from Air” by Emily Dickinson can express some of the same philosophical and political concepts you might articulate in an essay. Because good poetry is about precision of language, you can express a whole philosophy in very few words if you choose them carefully. Even seemingly light poetic forms like nursery rhymes or a silly rhyming limerick can communicate big, bold ideas. You just have to choose the right words.

- Paint with words. When a poet paints with words, they use word choice to figuratively “paint” concrete images in a reader’s mind. In the field of visual art, painting pictures of course refers to the act of representing people, objects, and scenery for viewers to behold with their own eyes. In creative writing, painting pictures also refers to producing a vivid picture of people, objects, and scenes, but the artist’s medium is the written word.

- Familiarize yourself with myriad forms of poetry. Each different form of poetry has its own requirements—rhyme scheme, number of lines, meter, subject matter, and more—that make them unique from other types of poems. Think of these structures as the poetic equivalent of the grammar rules that govern prose writing. Whether you’re writing a villanelle (a nineteen-line poem consisting of five tercets and a quatrain, with a highly specified internal rhyme scheme) or free verse poetry (which has no rules regarding length, meter, or rhyme scheme), it’s important to thrive within the boundaries of the type of poetry you’ve chosen. Even if you eventually compose all your work as one particular type of poem, versatility is still a valuable skill.

- Connect with other poets. Poets connect with one another via poetry readings and perhaps poetry writing classes. Poets in an artistic community often read each other’s work, recite their own poems aloud, and provide feedback on first drafts. Good poetry can take many forms, and through a community, you may encounter different forms that vary from the type of poem you typically write—but are just as artistically inspiring. Seek out a poetry group where you can hear different types of poetry, discuss the artform, jot down new ideas, and learn from the work of your peers. A supportive community can help you brainstorm ideas, influence your state of mind as an artist, and share poetry exercises that may have helped other members of the group produce great poetry.

Conclusion

Poetry is a form of art. It has many rules and regulations for writing it, and it’s not easy to follow them all. However, if you follow them attentively, your poetry work will be better appreciated by your readers.